On the 4th March 2023, the 5th Belmarsh Tribunal was held in the Great Hall of the Sydney University

Transcript-Sydney-Belmarsh-TribunalRead more:

Progressive International Invitation

The Official Australian Website in Support of Julian Assange

On the 4th March 2023, the 5th Belmarsh Tribunal was held in the Great Hall of the Sydney University

Transcript-Sydney-Belmarsh-TribunalRead more:

Progressive International Invitation

Dated the 2nd January 2023, Jack Enadcott distributed a copy of his review of the book ‘The Trial of Julian Assange’ by Nils Melzer

Editor’s Note: This review expresses the opinions of Jack Endacott

Readers-Review-Trial-of-Julian-Assange-FinalJack Endacott can be contacted at ejendacott@gmail.com

On the 1st January 2023, ABC Global Affairs Editor John Lyons, made this extraordinary prediction

My expectation is in the next two months or so, Julian Assange will be released.

Covering Articles

Sydney Morning Herald byMatthew Knott

Independent Australia by John Jiggens

On the 24th December 2022, Matthew Knott writes in the Sydney Morning Herald

Supporters of Julian Assange have welcomed Kevin Rudd’s appointment as Australia’s ambassador to the United States, saying they are hopeful he will use the position to press the Biden administration to drop espionage charges against the WikiLeaks founder.

Assange remains in London’s Belmarsh prison in London as he fights a US attempt to extradite him to face charges over the publication of hundreds of thousands of classified documents and diplomatic cables relating to the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

As far back as 2010, when he was serving as foreign minister, Rudd had insisted that the US government and whoever leaked the documents should be held responsible for the disclosure rather than Assange.

In a 2019 letter to the Bring Julian Assange Home Queensland Network, Rudd said Assange would pay an “unacceptable” and “disproportionate” price if he was extradited to the US.

Rudd said he could not see the difference between Assange’s actions and the editors of American media outlets who reported the material, adding that the US had failed to secure classified information appropriately.

“The result was the mass leaking of sensitive diplomatic cables, including some that caused me some political discomfort at the time,” he wrote.

“However, an effective life sentence is an unacceptable and disproportionate price to pay. I would therefore oppose his extradition.”

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese appointed Rudd to the nation’s most prestigious diplomatic posting on Tuesday, saying he would “conduct himself in a way that brings great credit to Australia”.

Assange’s father John Shipton noted that Rudd’s views reflect those of Albanese, who last month said he had personally raised Assange’s case with US officials.

Lawyer Greg Barns, an adviser to the Australian Assange campaign, said: “The appointment of Kevin Rudd should assist Prime Minister Albanese push to end the US pursuit of Assange.

“Mr Rudd has been supportive of Julian’s position and we look forward to his being able to ensure there is an end to this case.”

Chelsea Manning, the former army soldier who leaked the classified material, was sentenced to 35 years in jail but had her term commuted after six years by then-president Barack Obama in one of his final acts in office.

Earlier this year Rudd blasted then-UK home secretary Priti Patel’s decision to certify Assange’s extradition to the US to face charges under the Espionage Act.

“I disagree with this decision,” Rudd said on Twitter.

“I do not support Assange’s actions and his reckless disregard for classified security information.

“But if Assange is guilty, then so too are the dozens of newspaper editors who happily published his material. Total hypocrisy.”

A spokesman for Rudd pointed to his past statements on the issue when asked for comment.

In a statement following his appointment, which will begin in March, Rudd said: “Our national interest continues to be served, as it has for decades past, by the deepest and most effective strategic engagement of the United States in the region.”

Read original article in The Sydney Morning Herald

On the 28th November 2022, La Monde first published an open letter signed by The New York Times , The Guardian , Le Monde , Der Spiegel and El Pais (Google translated from French)

Twelve years ago, on November 28, 2010, our five international press organs ( The New York Times, The Guardian, Le Monde, El Paisand Der Spiegel) joined together to publish, in collaboration with WikiLeaks, a series of revelations picked up by the media around the world.

More than 251,000 diplomatic cables from the United States Department of State were made public during this “Cablegate”, shedding light on several cases of corruption, diplomatic scandals and espionage operations on a global scale. .

As the New York Timeswrote at the time , the leaked documents told “the unvarnished story of how the government makes its most important decisions, those with the greatest human and financial cost to the country. Today, in 2022, this exceptional documentary source is still used by journalists and historians alike, who still find material there for the publication of unpublished revelations.

For the founder of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, this “Cablegate” and several other “leaks” or leaks of sensitive documents have had extremely serious consequences. On April 12, 2019, Julian Assange, under a US arrest warrant, was apprehended in London. For three and a half years now, he has been detained on British soil, in a high security prison which normally houses terrorists or members of groups linked to organized crime. He risks being extradited to the United States, where he faces a sentence of up to one hundred and seventy-five years in a very high security prison.

Our group of editors and managing editors, all of whom have had the opportunity to work with Julian Assange, found it necessary to publicly criticize his attitude in 2011 when uncensored versions of the diplomatic cables were made public, and some of us remain concerned about the allegation in the US indictment that he aided in the computer intrusion into a classified “defense-secret” database. But we stand together today to express our deep concern over the endless legal proceedings that Julian Assange is facing for collecting and publishing confidential and sensitive information.

The Obama-Biden administration, in power when WikiLeaks was published in 2010, refrained from suing Julian Assange, explaining that many journalists from several major media should also have been prosecuted. This position recognized freedom of the press as crucial, regardless of the unpleasant consequences.

But this vision of things has evolved under the mandate of Donald Trump: the Department of Justice now relies on a law dating back more than a century, the Espionage Act of 1917. Conceived during the First World War to be able to sue would-be spies, this federal law had never been used against journalists, media outlets or broadcasters. Such an indictment sets a dangerous precedent, threatens the freedom of information and risks reducing the scope of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

In a democracy, one of the fundamental missions of an independent press is to hold governments accountable.

Collecting and disseminating sensitive information is likewise an essential part of a journalist’s day-to-day work, when such disclosure proves to be in the public interest. If this work is declared criminal, then not only the quality of public debate but also our democracies will be considerably weakened.

Twelve years after the first publications linked to “Cablegate”, the time has come for the United States government to drop its charges against Julian Assange for having published secret information.

Publishing is not a crime.

Translated from English by Lucas Faugère.

This text is signed by the editors of: The New York Times , The Guardian , Le Monde , Der Spiegel , El Pais .

Read Original Articles in

La Monde

New York Times

The Guardian

El País

Der Spiegel

and many many other news papers world wide

The articles in La Monde covering the Assange Saga

WikiLeaks: those responsible for “Cablegate” are to be sought in Washington

It is high time to act before Julian Assange pays with his life the price of our freedoms

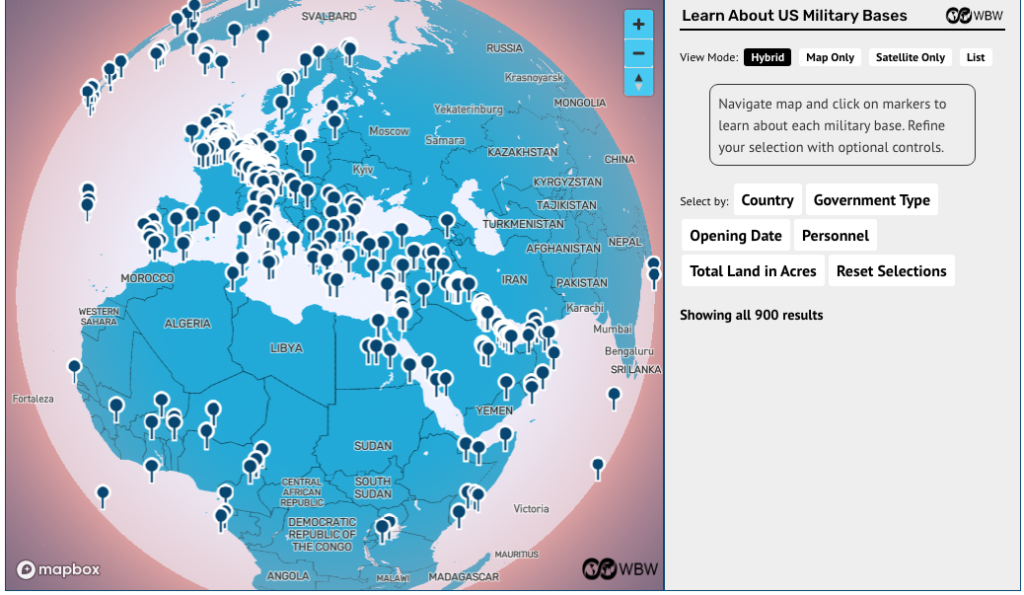

World Beyond War have published map of US Military bases around the world.

The United States of America, unlike any other nation, maintains a massive network of foreign military installations around the world.

How was this created and how is it continued? Some of these physical installations are on land occupied as spoils of war. Most are maintained through collaborations with governments, many of them brutal and oppressive governments benefiting from the bases’ presence. In many cases, human beings were displaced to make room for these military installations, often depriving people of farmland, adding huge amounts of pollution to local water systems and the air, and existing as an unwelcome presence.

Static image of the dynamic map on Beyond War web site.

Read original article World Beyond War

Read original article in World Beyond War

On the 13th Novembers 2022, Luisana Castro writes on Fuser News ( Google Translation from Spanish )

The production shows that Assange has been targeted to divert public attention from what WikiLeaks has revealed.

This Sunday, the film Ithaka, which deals with the search for John Shipton, father of the founder of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange , to save his son, private , opens in New York City, United States (USA). of freedom in the maximum security prison of Berlmarsh, in London, for more than three years.

Since the tragedy of the activist began, the media have focused attention on politics and the law, leaving aside the human part of Assange, which involves his family circle.

The same is true of the cyberactivist’s supporters, who also sometimes overlook the person and focus instead on the bigger issues at stake, reports an article published in the Consortium News by Joe Lauria.

Consortium News, the outlet that has provided perhaps the most comprehensive coverage of the WikiLeaks publisher’s Espionage Act indictment, has also focused more on the case and less on the man.

The film Ithaka, directed by Ben Lawrence and produced by Assange’s brother Gabriel Shipton, humanizes the Australian activist and reveals the impact his ordeal has had on those closest to him. It shows the legal and political complexities of the case and its background.

The title of this tape comes from the poem of the same name by Constantino Cavafis, about the pathos of an uncertain journey. It reflects Shipton’s travels across Europe and the United States in defense of his son, arguably the most important journalist of his generation.

The story begins as Shipton arrives in London to see his son behind bars for the first time after a new Ecuadorian government lifted the publisher’s asylum rights, leading to London police removing him from the embassy in April 2019.

In the film, the big issues involved transcend the individual: war, diplomacy, official deceit, high crimes, an assault on press freedom, and the core of what little democracy remains in a militarized system corrupted by government. money.

The production shows that Assange has been targeted to divert public attention from what WikiLeaks has revealed, from what the state is doing to him to hide the impact on media freedom and courtroom standards.

The creators of the audiovisual to be released in the US placed the main focus of the film on the extradition hearing at Westminster Magistrates Court that began in February 2020 and ended in September of that year. In the lead up to the hearing, Shipton explains how important family is to him at this stage of his life.

The film explores the romance between Stella Morris and Julian Assange, which began inside the Ecuadorian embassy in 2015, showing grainy CIA-ordered surveillance footage of them meeting.

During his appearance on the video, Morris talks about his decision to start a family while there were no charges against him, no known investigation, and after a UN panel ruled that he was being arbitrarily detained and should be released.

Laurence, the writer points out that in another scene, “we see Assange briefly in prison during a video call on Stella’s phone. She shows him the sunlight and he enjoys the sound of a horse in the street.” During the recording of a BBC interview, Stella is seen to break down emotionally.

“Extraditions are 99% politics and 1% law,” says Stella. “He just needs to be treated as a human being and not be denied his dignity and his humanity, which is what has been done to him,” Assange’s wife notes in the film.

Read original article in FuserNews

On the 29th October 2022, John Shipton accepts the Roberto Morrione award in Turin, Italy.

Yesterday in Turin, as part of the award named after Roberto Morrione, an exciting debate took place on the story of Julian Assange. As is well known, the Australian-born journalist risks being extradited from Great Britain to the United States where he will be sentenced to 175 years in prison. A “monster” was built at the table, guilty of having stuck his nose in the arcana and omissions of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as in the reserved cables of the chancelleries or in the Guantanamo scandal. Whoever accused him – the president of the Federation of the Juliet press always remembers – goes around giving well-paid conferences, whoever has allowed to know the truth is in fact sentenced to death. Moreover, after thirteen years of via crucis, the psychophysical conditions of the founder of WikiLeaks are very worrying. In these days the defense college, of which Assange Stella Moris’s lawyer wife is a part, is awaiting the judgment of the English courts on the possibility of appealing the decisions so far favorable to extradition. Even if the way to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights remains open. The situation was explained well by the journalist and writer Stefania Maurizi, whose volume “The secret power” (the updated edition in English is out) was the point of reference for the counter-narrative. A long guilty silence has broken, while it is becoming clear that Assange is the scapegoat of a real repressive tendency: today he, tomorrow all and all those who do not bend their backs. Gian Giacomo Migone, former president of the Senate Foreign Commission in three legislatures, intervened on the same wavelength, adding a clear criticism to the whole of Sweden, where the judicial parable took place. The central event of the evening was the delivery by the President Carlo Bartoli of the honorary card of the Order of Journalists for his son to Assange’s father John Shipton. It was a moving moment, with the large audience standing to applaud: a small symbolic compensation in the face of a blatant injustice. Bartoli underlined how Assange’s feared defeat would set a very serious precedent for the right to press and freedom of information. Among other things, as reiterated in numerous Italian and European judgments, it is a journalist’s duty to publish public news without hesitation, in order to respond to the citizens’ right to be informed. In conclusion, Mara Filippi Morrione also spoke about it, the soul of the event dedicated to those who taught entire generations to consider journalism not only a profession, but also and above all a civil ethics. Assange was, among other things, appointed Guarantor by the audiovisual archive of the workers’ and democratic movement, as the writer announced. The “NoBabaglio Network” and the “Coordination for Constitutional Democracy” signed up to the initiative. Finally, some of the more than 80 videos of testimony for the freedom of the founder of WikiLeaks collected by the “My voice for Assange” Committee, coordinated by the Sapienza professor Grazia Tuzi absent due to indisposition, were screened. “Articolo21” will continue the campaign with incessant determination, a crucial step in this season of technical tests of authoritarian sovereignties.

Read original article in Italy 24 Press News

More about the Roberto Morrione award ( in Italian )

They are unable to find any evidence that linking Julian Assange to Manning’s account.

On the 20th October 2022, Kevin Gosztola reports in The Dissenter on Chelsea Manning’s new book ‘Readme.txt’

In the United States government’s case against WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, prosecutors claim that he communicated with US Army whistleblower Chelsea Manning through an encrypted chat client known as Jabber.

Prosecutors highlight several alleged exchanges between Manning and a username, or handle, associated with Assange. Yet they have never been able to definitively prove that Manning was chatting with Assange, and Manning’s new book, README.txt, further complicates their case.

Manning recalls in February 2010 that she told a chat room with individuals she believed to be associated with WikiLeaks that they could expect an “important submission.” She received a response from someone with the handle “office,” who changed their handle to “pressassociation.”

At this time, Manning had prepared what became known as the “Collateral Murder” video for submission to WikiLeaks. The video showed an Apache helicopter attack in Baghdad by US soldiers that killed two Reuters journalists, Saeed Chmagh and Namir Noor-Eldeen, and Saleh Matasher Tomal, a good Samaritan who pulled up in a van and tried to help the wounded.

…

In the indictment against Assange, prosecutors state, “No later than January 2010, Manning repeatedly used an online chat service, [Jabber], to chat with Assange, who used multiple monikers attributable to him.”

“The grand jury will allege that the person using these monikers is Assange without reference to the specific moniker used,” according to the indictment.

This illustrates the intent of US prosecutors to rely upon circumstantial evidence to tie Assange to the account, like they did during Manning’s court-martial. However, as was true during the court-martial, the government still cannot prove Assange was the WikiLeaks associate chatting with Manning under a “specific moniker.”

During a four-week extradition hearing in September 2020, Assange’s legal team had Patrick Eller, a command digital forensic examiner responsible for a team of more than eighty examiners at US Army Criminal Investigation Command headquarters, provide testimony to the UK district court. He had access to the court-martial record.

Eller said that he was unable to find any evidence that linked Assange to the “Nathaniel Frank” account.

Now, in a government affidavit from 2019, assistant US attorney Kellen Dwyer claimed the US has a witness that the FBI interviewed in 2011, who will testify that Assange used the pressassociation account. The witness is a woman who was “romantically involved” with Assange and met him in Berlin in 2009.

Dwyer also indicates that Siggi Thordarson, an FBI informant from Iceland who is a diagnosed sociopath and serial criminal, will testify that Assange used “pressassociation” as “one of his online nicknames.”

None of this featured in the extradition proceedings, and Crown prosecutors did not contest Mark Summers QC, an Assange attorney, when he had Eller address the lack of proof that Assange used the account that chatted with Manning.

Read original article in The Dissenter

More abot Chelsea Mnning and her book in the Guardian – README.txt by Chelsea Manning review – the analyst who altered history

Chelsea’s book is readily available online such as the Nile (selected on price)

On the 19th October 2022, Jennifer Robinson addressed the Australian National Press Club

Available on ABC Iview

and followup interview with Chris Mitchell on ABC NewsRadio

Thank you for your warm welcome and introduction, Laura.

It is a great pleasure to be with you at Australia’s National Press Club on Ngunnawal land. I pay my respect to Ngunnawal elders past, present and emerging – and to all First Nations people here today and joining us remotely.

I’d like to also acknowledge the presence today of those who have supported Julian and his family – including:

I have been working on Julian Assange’s defence and talking about its implications for freedom of the press and democracy for more than a decade.

You might have heard some media soundbites from me on these themes over the years: about the stark injustice that Julian faces 175 years in prison for committing acts of journalism; about how the US seeks to condemn him to life in prison for the very same publications for which he has won awards the world over – including the Walkley Award for Most Outstanding Contribution to Journalism and the Sydney Peace Prize Medal; and that his prosecution sets a dangerous precedent for free speech and journalists everywhere.

But having an opportunity to elaborate is rare, so my thanks to the National Press Club for giving me this time with you today.

I’m often asked how Julian is, so let me start there:

I don’t know how much longer he can last.

The world was shocked by his appearance when he was arrested in 2019. I wasn’t.

For over 7 years, I had been watching his health decline inside the Ecuadorian embassy where he was protecting himself from US extradition.

After years of government statements and media commentary claiming Julian was paranoid and should just leave the embassy, some were surprised when Julian was served with a US extradition request.

I wasn’t. It was exactly what we had been warning about for a decade.

For the past 3.5 years, Julian has been in a high security prison in London – and I have watched his health decline even further.

Then last year, during a stressful court appeal hearing, Julian had a mini stroke.

As the prosecution was deriding the medical evidence of Julian’s severe depression and suicidal ideation – and the risk to his life – those with video access saw Julian in a blue room in Belmarsh with his head in his hands.

I’ve seen Julian on some pretty bad days, but he looked terrible. I was alarmed. And for good reason.

As it turned out, he had just had – or was experiencing as we watched – a mini stroke, often the harbinger for a major stroke.

Once again, we were witnessing Julian’s health deteriorate in real time.

Julian’s wife Stella waits anxiously for the phone call she dreads. As she has said, Julian is suffering profoundly in prison – and it is no exaggeration to say he may not survive it.

***

Unless a political resolution is found – and this case has always been political – Julian will be detained for many years to come.

It is impossible to accurately predict the timeline, but here is a brief overview of where we are and what the legal process ahead looks like.

After a year-long extradition hearing process, interrupted by COVID outbreaks, Julian won his case in early January 2021. If extradited to the US, he would be placed under prison conditions known as Special Administrative Measures – or SAMs – which has been described as the darkest black hole of the US prison system. The magistrate ruled that Julian’s extradition would be oppressive because the medical evidence shows that if extradited and placed under SAMs, he would suicide. So she barred his extradition.

But the Trump administration appealed – and in its last days, sought to get around the court decision and shift the goal posts by offering an assurance that Julian would not be placed under SAMs.

As Amnesty International has said, US assurances aren’t worth the paper they’re written on.

But in Julian’s case it’s even worse that that because the US assurance was conditional: the US only promised not to place him under SAMs unless they decide he later deserves it.

And who would decide? The CIA. And he would have no right to appeal their decision.

Before the US government appeal was heard, we learned – thanks to important investigative journalism – that the CIA had planned to kidnap and kill Julian.

Yes: let’s pause there for a moment.

The CIA had planned to kidnap and kill an award-winning Australian journalist in London.

Again: the Central Intelligence Agency had plans in place to send someone to London to kidnap and assassinate Julian Assange. We know this because of an investigation based on interviews with 30 official US government sources.

And this is the intelligence agency which has the power to place Julian, once extradited to the US, under prison conditions that doctors say would cause his suicide.

When the news broke, I thought – finally – this has got to end the case. But no.

The British courts accepted the US assurance and ruled Julian could be extradited despite these circumstances.

In June, the British Home Secretary ordered his extradition.

We have filed an appeal and we should learn soon whether the High Court will grant permission and hear it.

If it does, we can expect a process that could take years – through the High Court, and to the UK Supreme Court. If we lose, we will appeal to the European Court of Human Rights – that is, if the conservative British government doesn’t remove its jurisdiction before we are able to.

If our appeal fails, Julian will be extradited to the US – where his prison conditions will be at the whim of the intelligence agencies which plotted to kill him. He will face an unfair trial and once convicted, it could take years before a First Amendment constitutional challenge would be heard before the US Supreme Court.

Another decade of his life gone – if he can survive that long.

And that is why I am here.

This case needs an urgent political solution. Julian does not have another decade to wait for a legal fix. It might be surprising to hear me, as a lawyer, say this: but the solution is not legal, it is political.

When you hear politicians or government officials in the UK or US or in Australia using language like due process and rule of law – this is what they are talking about. Punishment by legal process. Bury him in never-ending legal process until he dies.

In fact, there’s been very little “rule of law” or “due process” in what’s been inflicted on Julian. As we argue in our appeal, the case has been rife with abuse.

The case against him is unprecedented – it is the first time in history a publisher has faced prosecution for journalism under the Espionage Act. And the US is going to argue that, as an Australian citizen, Julian is not entitled to constitutional free speech protection at all.

The UK-US extradition treaty prohibits extradition for political offences – and yet the US is purporting relying on this treaty to extradite Julian under the Espionage Act. Espionage is a political offence.

We have seen the fabrication of evidence against him – the US’ key witness in Iceland has admitted he lied but the US continues to press charges based on his evidence. And its indictment deliberately misrepresents the facts.

We have seen unlawful surveillance of Julian, on me personally and his lawyers, on his medical treatment, and the seizure of legally privileged material. At the extradition hearing, we heard evidence from Daniel Ellsberg, the revered leaker of the Pentagon Papers. Ellsberg explained that his prosecution under the Espionage Act by the Nixon administration was thrown out – with prejudice – for far less abuse than Julian has faced. But Julian’s prosecution commenced under the Trump administration – and now continues under Biden. What does that say about our civil liberties and our democracies in 2022?

The list of abuse goes on and on. [take a breath…]

As a lawyer working on human rights cases, it’s important to remain focused on the principles at stake and the work at hand. An essential part of the job is being dispassionate and level-headed in the face of injustice.

But it has become harder and harder over the years to remain unaffected by what Julian is being put through – as a human being and fellow Australian.

In 2019, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Nils Melzer, reported his findings on Julian’s case and concluded Julian had been subjected to torture. Years before, we had made a complaint to Melzer’s mandate – but we heard nothing back. Melzer would later admit he had ignored our complaint because, like many, he was prejudiced against Julian after years of government propaganda and media coverage attacking Julian’s reputation.

But in 2019, he agreed to read our complaint. And what he read shocked him and forced him to confront his own prejudice. He has since written a book about what he learned, The Trial of Julian Assange, which I highly recommend.

In his UN findings, Melzer put it this way:

‘In 20 years of work with victims of war, violence and political persecution I have never seen a group of democratic States ganging up to deliberately isolate, demonise and abuse a single individual for such a long time and with so little regard for human dignity and the rule of law’.

It hasn’t always been easy to remain dispassionate in the face of this persecution – and its impact on Julian and his family.

Julian’s has two small children, Gabriel and Max, who are just 5 and 3. When they tell me about going to see Daddy “in the queue” – they are talking about seeing him in prison. They call it “the queue” because of the security queue they have to stand in, as guards pat down and search their little bodies, checking inside their ears and mouths, in their hair and in their shoes, before they can see their father.

It is heart-breaking.

Due to COVID restrictions, Julian wasn’t allowed to see his children for 6 months. When they were finally let into see him, ongoing prison restrictions meant there was a period he wasn’t allowed to touch them or give them a cuddle. Explain that to a child.

It is heart-breaking.

Last week, thousands of people linked hands to form a human chain around British Parliament in an inspiring protest to demand Julian’s freedom. The kids came to the protest and I walked with them around the chain. They were wearing their “Free My Dad” t-shirts, and chanted along with the crowd “Free Julian Assange”.

It is heart-breaking.

I say this because I want to remind you all today of the very real, human consequences of this case.

***

But what is Julian in prison for? Why are he and his family being put through all of this?

The events that led to Julian’s indictment started in a room similar to this one.

On 5 April 2010, at the National Press Club in Washington DC, WikiLeaks shared the Collateral Murder video with the world. It put WikiLeaks – and Julian – on the map in all kinds of ways.

As you know, it showed the murder of civilians, children and journalists by US forces in Iraq. A war crime, which the US authorities then tried to cover up.

An Australian journalist, Dean Yates, was the head of Reuters in Iraq at the time. He sought answers about what had happened to his colleagues. The US claimed their forces had complied with their rules of engagement. That was a lie. Freedom of Information requests were rejected – and Yates and Reuters were denied the truth.

It was only after the video and rules of engagement were published by WikiLeaks that the world understood what happened.

I want to emphasise here: Julian is being prosecuted for publishing evidence about the murder of your journalist colleagues in Iraq.

After the release of Collateral Murder came the Afghan War Diary, the Iraq War Logs and the State Department Cables. In each of these releases, WikiLeaks pioneered global collaborations between journalists on a scale never seen before. Working together with WikiLeaks, journalists from mainstream media outlets, analysed large sets of data, identifying patterns and trends to understand what was really happening, and tell the story.

The publications showed that thousands more civilians were killed in American wars than the US government had ever admitted. They showed evidence of war crimes, extrajudicial killings, and torture by US forces, western governments and their autocratic regime allies. They revealed the dense networks of support between those governments and major corporations and the extent to which foreign and trade policy was driven by corporate interests.

Journalism like this, at its core, is about subjecting power to scrutiny, and holding it accountable.

And the powerful didn’t like it. WikiLeaks was responsible for hundreds – even thousands – of stories about how power really works in Washington, in London, in Canberra, in capitals across the world – about what it means in the streets and homes of people in countries like Iraq and Afghanistan – and about the price that is paid for the application of power in shattered lives and dead and broken bodies.

Rather than shame, WikiLeaks provoked rage – rage that journalism was exposing the powerful.

The Obama administration opened a criminal investigation which Australian diplomats reported was unprecedented in size and scale.

But the Obama administration ultimately did not indict Julian. Their concern was the “New York Times problem”: that is, that prosecuting Julian would mean criminalising what the New York Times does every day.

President Trump had no such qualms. After all, he called the media, “the enemy of the people” and said he wanted to see reporters in prison. And the result is an indictment against Julian which describes – and criminalises – routine journalistic practices.

But let’s not forget that Trump was willing to play politics with this prosecution.

Back in 2017 – before Julian had been indicted – a Congressman came to visit Julian in the embassy to offer him a deal.

Julian asked me to attend to observe the meeting and I would later give evidence about it for his extradition hearing.

It was at the height of the Mueller investigation – about Russian interference in the 2016 election – when President Trump was a subject of the investigation. Julian had already stated in public that the material was not from a government source. But Trump clearly wanted to know more.

Congressman Dana Rohrabacher made clear that President Trump was aware of and had approved of him coming to discuss a proposal.

It was what he called a “win-win solution” that would allow Julian to “get on with his life”. Julian was asked to identify the source of the 2016 election publications – which the Congressman explained would solve Trump’s political problems and help him put a stop to the Mueller investigation. In return, Julian would receive a pardon or some form of protection against US extradition.

Julian refused to provide the identity of his source.

A publisher’s promise to sources is solemn, as would be well understood in this room, even if it carries a cost.

Trump too, made good on his promise, his administration indicting Julian after he refused to name his source.

Julian has had other opportunities to act in his own interest rather than in the interests of democracy and free speech – and he has always put his own interests second.

And the result is an indictment against him which threatens free speech and democracy. The Freedom of the Press Foundation calls Julian’s prosecution “the most terrifying threat to free speech in the 21st century”. And that is not an exaggeration.

One of the 18 charges relates to taking measures to protect the identity of a source. The remaining 17 charges, all brought under the Espionage Act, relate to receiving and publishing information – and there is no public interest defence.

And around the world the media has responded – The New York Times,

the Washington Post, and the Guardian have warned that the US is criminalising public interest journalistic practices.

Journalists unions have responded – IFJ, MEAA, NUJ, have condemned the prosecution and called on the US to drop the charges.

[…]

Today, at the National Press Club of Australia, I want to make very clear: the Trump administration indicted Julian to send a message to the press. To deter journalism and publishing. Prosecuting Julian is intended to send a message to all of you.

With those reflections on the case against Julian, let me now turn to the implications for free speech and democracy.

***

Julian founded WikiLeaks with a mission statement – the goal is justice, the method is transparency. He could see that secrecy breeds injustice and that by shining a light, governments can be held accountable. He knew that transparency deters unlawful conduct and encourages better policy-making.

And he was right: WikiLeaks publications have been used in human rights cases the world over – including in some of my cases – to hold government accountable and enforce your rights.

Julian founded WikiLeaks to improve democratic accountability. As he says, we cannot act if we do not know. He wanted to provide the public with the information they need to make more informed democratic choices.

And he was right: Amnesty International credited Wikileaks with sparking the Arab Spring – and democratic movements for change.

Julian once said, if lies can start an unlawful war, then the truth can stop it.

And again, he was right: WikiLeaks publications led to the Iraqi Parliament removing immunity for US troops in occupied Iraq – which led to the withdrawal of US troops.

For this work, he has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize every year for the past decade – that is more times than any other Australian.

WikiLeaks was out in front in recognising the implications of the internet for journalism and its promise and potential for protecting sources with anonymity guaranteed by technology. Julian created technology that has been replicated by media organisations the world over to protect themselves and their sources.

For this work, Julian has won journalism awards around the world. And for this work, he faces life in prison.

This injustice could not be more obvious. No matter how long the US government drags this out, we must all resist the normalisation of this treatment of an Australian journalist and publisher – or he won’t be the last of you to suffer.

As the President of the IFJ said this week, ‘If Julian Assange is jailed in the US, there is not a journalist on earth who will be safe”.

And she is right.

If Julian is extradited, the precedent being set means that any journalist, anywhere in the world, can be extradited and prosecuted in the US for publishing truthful information in the public interest. Would we stand by and accept this if it was Russia or China doing the same?

*********

I want to make a few concluding remarks about Julian’s future. About what the Australian government can do. And about what you can do.

Those who resolve Julian’s case – by securing his release – will be remembered well in the books that will be written about it. They will be on the right side of history.

Australians remember well who brought David Hicks home. We remember well who got Peter Greste, Melinda Taylor and James Ricketson out of overseas prisons. We remember well who got Kylie Moore-Gilbert out of prison in Iran. If we can put an end to an espionage case against an Australian citizen in Iran, we can do it in respect of an equally outrageous espionage case in the US.

And what a great day that was, when Kylie was free.

I look forward to another great day, when this Australian Prime Minister and this government gets Julian out of prison.

For more than a decade we have had nothing but silence and complicity from consecutive Australian governments. Government after government – on both sides of politics – did not have the courage to speak to our close ally and act to protect an Australian citizen and journalist.

We now have a Prime Minister who has said, and I quote, “Enough is enough”.

“I fail to see what purpose is being served by the ongoing incarceration of Julian Assange. A heavy price has been paid.”

I couldn’t agree more.

We now need to see action.

We all want to see our Prime Minister taking questions at a press conference about Julian’s release – rather than about Julian’s death in custody.

And what will help force the government bring this to a close? You – the journalists in this room.

You, above all people, are able to differentiate between publishing and espionage; a distinction that the US government and its allies seem intent on erasing.

You have the unique opportunity and responsibility of facing the Prime Minister and his colleagues day after day. You can ask what is being done and when it is we will see Julian brought home. Ask them this – the Attorney General, the Foreign Minister, the Prime Minister – at every press conference until Julian is free.

If we don’t see that day, Julian Assange won’t be the last of your colleagues to have his life destroyed in this line of work.

What will also help force our government to do the right thing and bring Julian home?

You – the public.

Protest, write to your MP, write to the Prime Minister, turn up at their offices and demand action. Working for democratic accountability is why Julian is in prison – and I believe democratic accountability can help him get out of it.

So hold our government to account. And let’s bring Julian Assange home. Thank you.