On the 29th March 2024, Craig Murray posted his assessment of the latest Judgement in the High Court Appeal in the Assange Case

The latest judgment by the High Court in the Assange case achieved completely the objectives of the UK and US states. Above all, Julian remains in the hell which is Belmarsh maximum security prison. He is now safely there alone and incommunicado, from the authorities’ point of view, for at least several more months.

Importantly, the United States has managed to keep him detained without securing his actual appearance in Washington. It is crucial to grasp that the CIA, who are very much controlling the process, do not actually want him to appear there until after their attempt to secure the re-election of Genocide Joe. No matter what your opinion of Donald Trump, there is no doubt the CIA conspired against him during his entire Presidency, beginning with the fake Russiagate scandal and ending with their cover-up of the Hunter Biden laptop story. They do not want Trump back.

Biden is politically in deep trouble. Biden’s lifelong political support for Israel has been unwavering to the point of fanaticism. In the process he has collected millions of dollars from the Zionist lobby. That always seemed a source of political strength in the United States, not of weakness.

The current genocide in Gaza has changed all those calculations. The sheer evil and viciousness of the Israeli state, the open and undisguised enthusiasm for racist massacre, has achieved the seemingly impossible task of turning much American public opinion against Israel.

That is particularly true among key elements of the Democratic base. Young people and ethnic minorities have been shocked that the party they have supported is backing and supplying genocide. The mainstream media have lost control of the narrative, when the truth is so widely available on mobile phones, to the point that the MSM have actually been forced to change course and occasionally tell truths about Israel. That also was unthinkable a few months ago.

Precisely the same groups who are outraged by Biden’s support for genocide are going to be alienated by the attack on a journalist and publisher for revealing true facts about war crimes. Assange is not currently a major public issue in the United States, because he is not currently in the United States. Were he to arrive there in chains, the media coverage would be massive and the issue unavoidable in the presidential election campaign.

The extradition proceeding has therefore had to be managed in such a way as to keep Assange locked in a living hell the whole time, without actually achieving the extradition until after the presidential election in November. As the years of hearings have rolled by this has become increasingly difficult for the British state to finesse on behalf of their American masters.

In this respect, and only in this respect, Dame Victoria Sharp and Lord Justice Johnson have done brilliantly in their judgment.

Senior British judges do not have to be told what to do. They are closely integrated into a small political establishment that is socially interlinked, defined by membership of institutions, and highly subject to groupthink.

Dame Victoria Sharp’s brother Richard arranged an £800,000 personal loan for then Prime Minister Boris Johnson, and subsequently became chairman of the BBC despite a complete lack of relevant experience. Lord Justice Johnson as a lawyer represented the intelligence services and the Ministry of Defence.

They did not have to be told what to do in this case explicitly, although it was very plain that they entered the two-day hearing process knowing nothing except a briefing they had been given that the crux of the case was the revelation of names of US informants in the Wikileaks material.

The potential danger of an appeal, the granting of which would achieve the United States’ objective of putting the actual extradition back beyond the election date, was that it would allow the airing in public of a great catalogue of war crimes and other illegal activity which had been exposed by Wikileaks.

Sharp and Johnson have obviated this danger by adjourning the decision with the possibility of granting an appeal, but only on extremely limited grounds. Those grounds would explicitly gag the defence from ever mentioning again in court inconvenient facts, such as United States war crimes including murder, torture and extraordinary rendition, as well as the plans by the United States to kidnap or assassinate Julian Assange.

All of those things are precluded by this judgment from ever being raised again in the extradition hearings. The politically damaging aspect of the case in terms of the Manning revelations and CIA behaviour has been cauterised in the UK.

There has been some confusion because the judgment stated that three grounds of possible appeal were open. But in fact this was really only two. The judgment states that freedom of expression under article 10 of the European Convention is adequately covered by the First Amendment protections of the US Constitution. Therefore this point can only be argued by the defence against extradition if the First Amendment will not be applied in the case.

The second ground of appeal which they stated may be allowed was discrimination by nationality, in that the prosecution has stated that as a foreign citizen who committed the alleged acts whilst outside of the United States, Julian may not have the protection of the First Amendment or indeed of any of the rights enshrined in the US Constitution.

So the first two grounds are in fact identical. Sharp and Johnson ruled that both would fall if an assurance were received from the government of the United States that Julian would not be denied a First Amendment defence on grounds of nationality.

The other ground on which an appeal may be allowed to go forward is the lack of an assurance from the United States that, following additional charges, Julian may not become subject to the death penalty.

I shall go on to analyse what happens now and the chances of success on any of these allowed appeal points, but I wish first to revisit the points which have not been allowed and which are now barred from ever being raised in these proceedings again.

The most spectacular argument in the judgment, and one which I trust will become notorious in British legal history, refers to the application to bring in new evidence regarding the US authorities’ illegal spying on Julian and plotting to kidnap or assassinate him.

There are any number of things in this case over five years which are so perverse that they have to be witnessed to be believed, but none has risen to this height and it would be a struggle for anybody to come up with anything in British legal history more brazen than this.

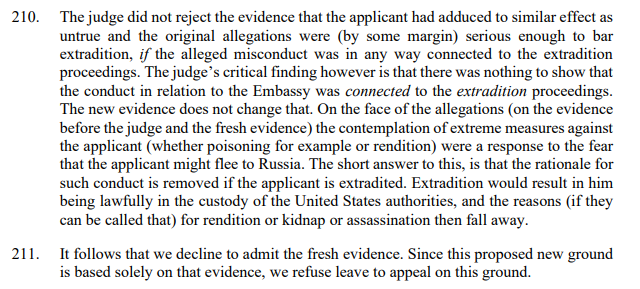

Judge Johnson and Judge Sharp accept that there is evidence to the required standard that the US authorities did plot to kidnap and consider assassinating Julian Assange, but they reason at para. 210 that, as extradition is now going to be granted, there is no longer any need for the United States to kidnap or assassinate Julian Assange: and therefore the argument falls.

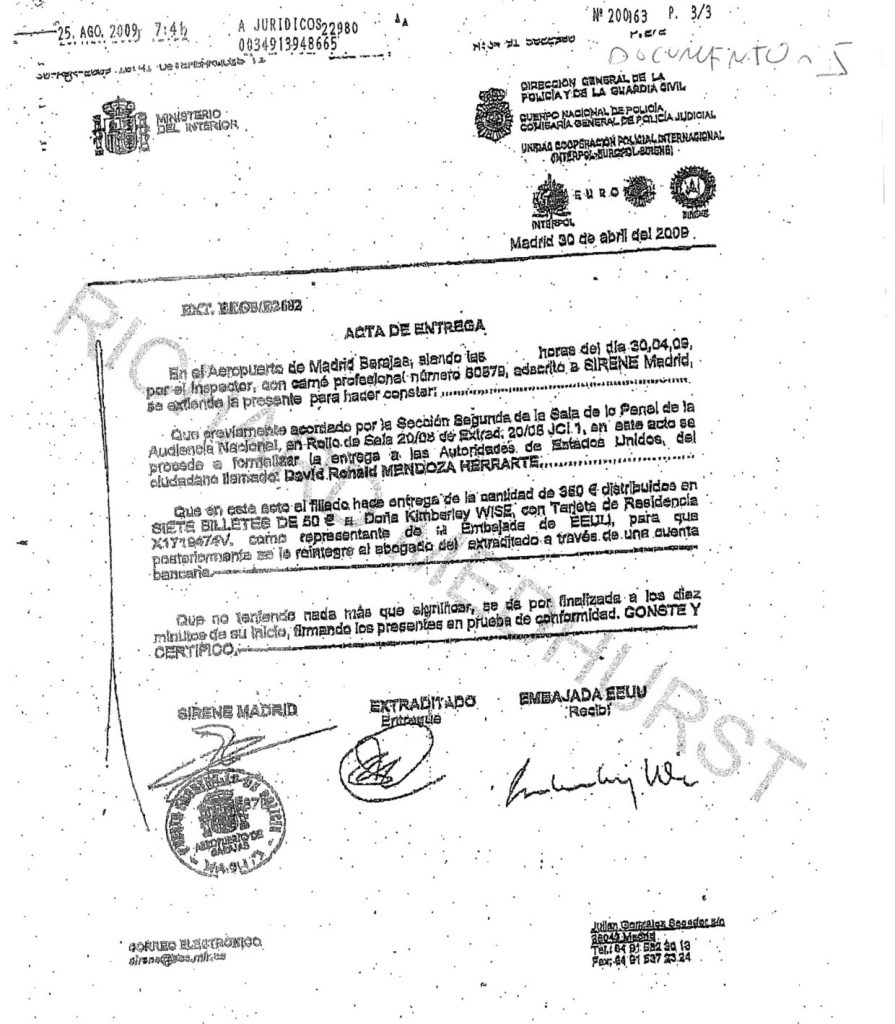

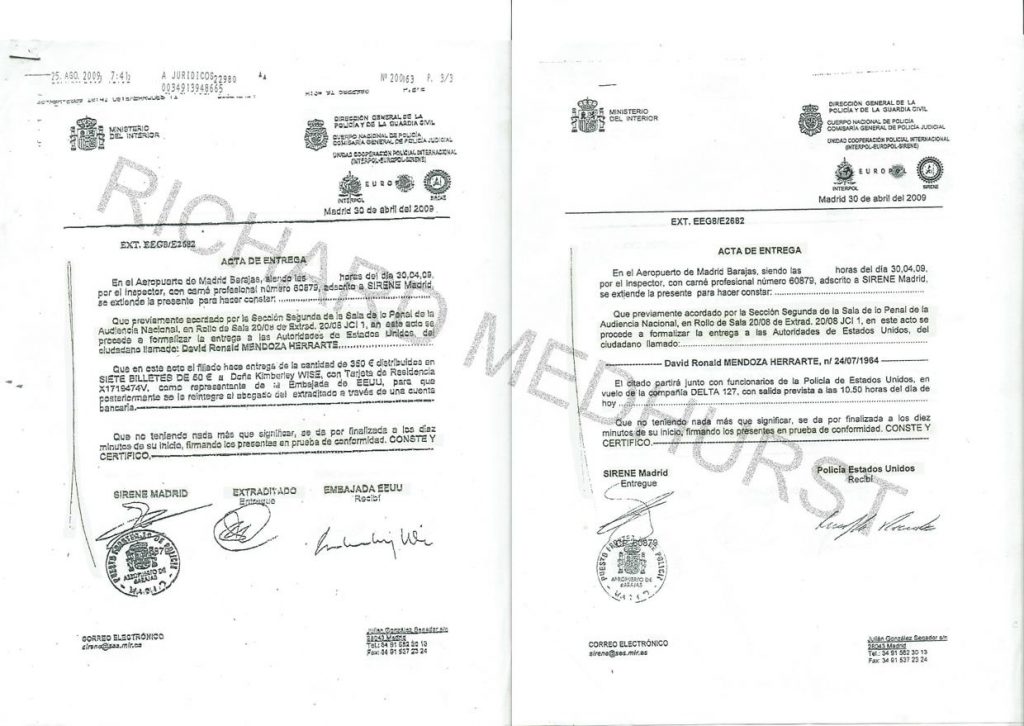

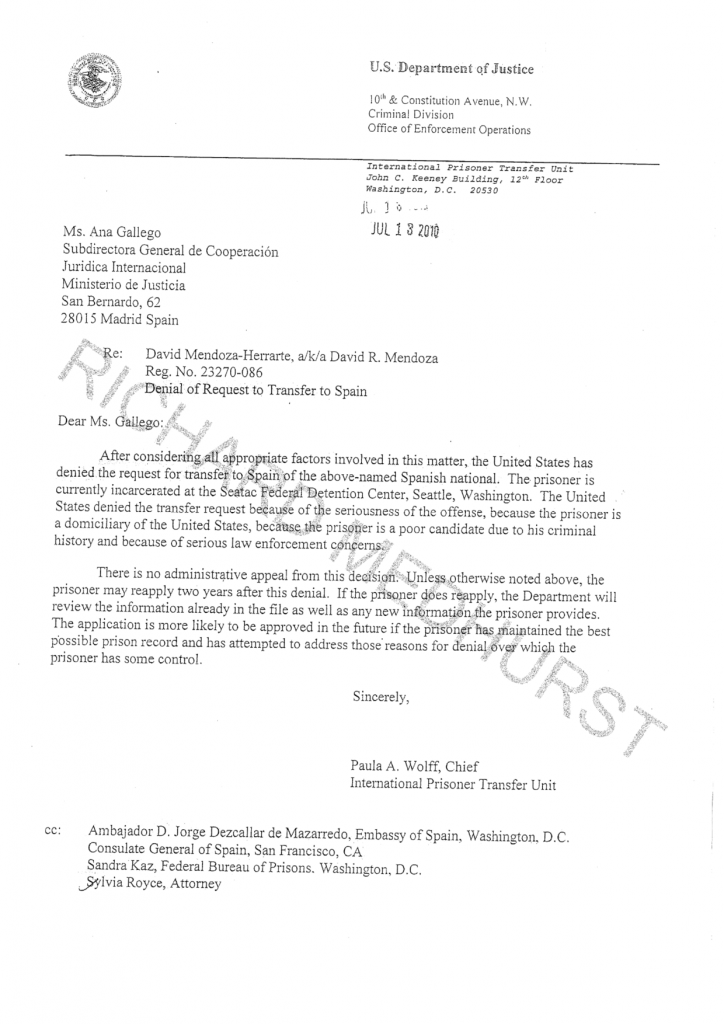

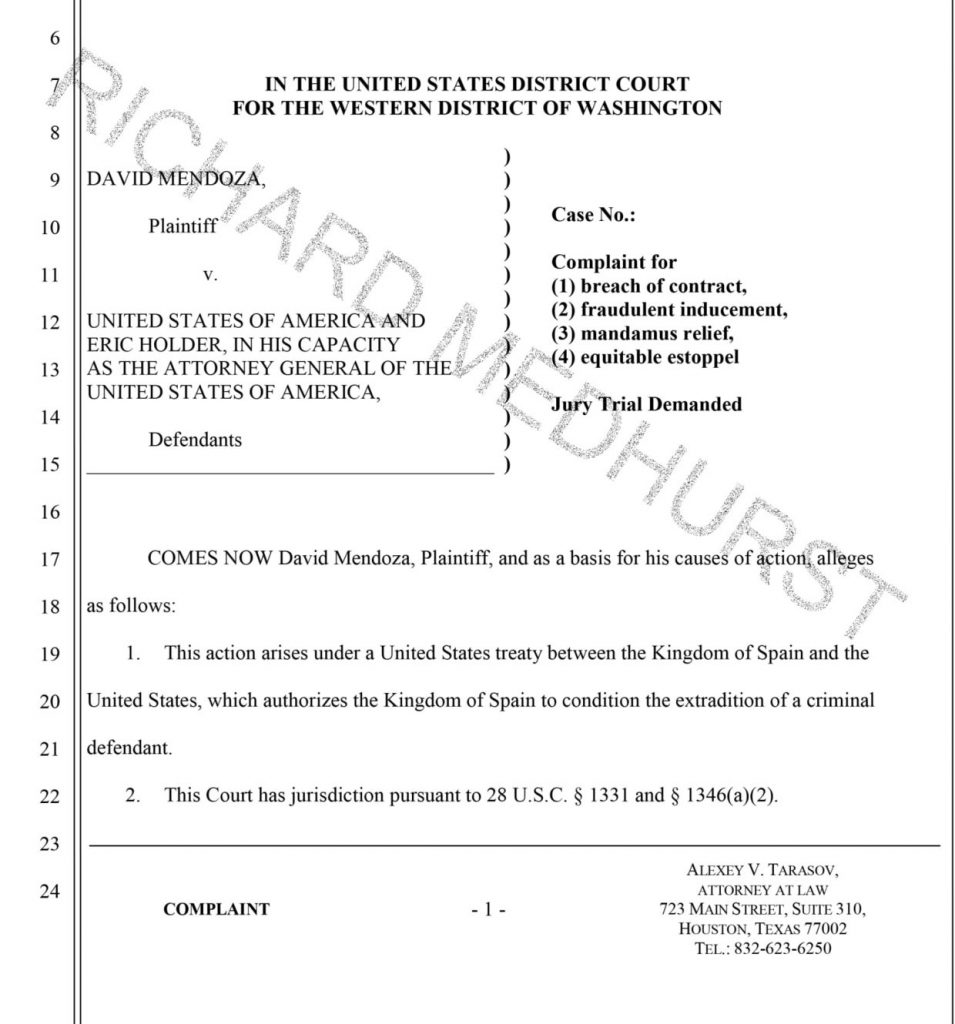

It does not seem to occur to them that a willingness to consider extrajudicial violent action against Julian Assange amounts to a degree of persecution which obviously reflects on his chances of a fair trial and treatment in the United States. It is simply astonishing, but the evidence of the US plot to destroy Julian Assange, including evidence from the ongoing criminal investigation in Spain into the private security company involved, will never again be allowed to be mentioned in Julian’s case against extradition.

Similarly, we are at the end of the line for arguing that the treaty under which Julian is being extradited forbids extradition for political offences. The judgment confirms boldly that treaty obligations entered into by the United Kingdom are not binding in domestic law and confer no individual rights.

Of over 150 extradition treaties entered into by the United Kingdom, all but two ban extradition for political offences. The judgment is absolutely clear that those clauses are redundant in every single one of those treaties.

Every dictatorship on Earth can now come after political dissidents in the UK and they will not have the protection of those clauses against political extradition in the treaties. That is absolutely plain on the face of this ruling.

The judgment also specifically rejects the idea that the UK court has to consider rights under the European Convention of Human Rights in considering an extradition application. They state that in the United States—as in other Category 2 countries in terms of the Extradition Act 2003—those rights can be presumed to be protected at trial by the legislation of the country seeking extradition.

That argument abdicating responsibility for application of the ECHR is one that is not likely to be accepted if this case ever gets to Strasbourg (but see below on the possibility of that happening).

By refusing to hear the freedom of expression argument, the court is ruling out listening to the war crimes exposed by the material published and hearing that the publication of state level crime is protected speech. That entire argument is now blocked off in future hearings and there will be no more mention of US war crimes.

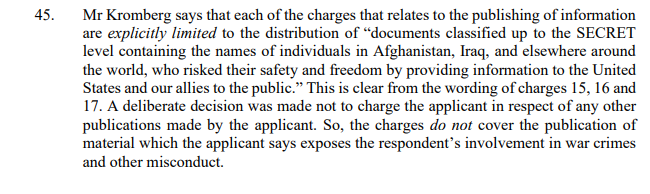

The judges accept—hook, line and sinker—the tendentious argument that Julian is not being charged with the publication of all of the material but only with those documents within the material which reveal the name of US informants and sources. As I reported at the time, this was plainly the one “fact” with which the judges had been briefed before the hearing.

That it is a legitimate exercise to remove entirely from consideration the context of the totality of what was revealed in terms of state crimes, and to cherry pick a tiny portion of the release, is by no means clear; but their approach is in any event fatally flawed by a complete non sequitur:

At para. 45 they argue that none of the material revealing criminal behaviour by the United States is being charged, only material which reveals names. Their argument depends upon an assumption that the material revealing names of informants or sources does not also reveal any criminal behaviour by the United States. That assumption is completely and demonstrably false.

Let us now turn to the grounds on which a right to appeal is provisionally allowed, but may be cancelled in the event of sufficient diplomatic assurances being received from the United States.

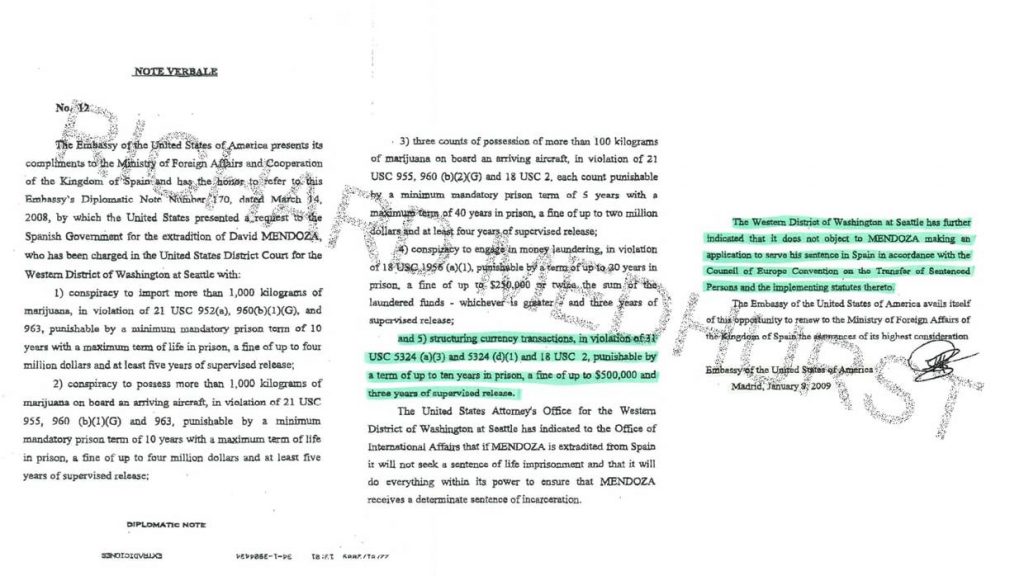

To start with the death penalty, which has understandably drawn the most headlines: it astonishes me, as this argument has been in play now for several months, that the United States has not provided the simple assurance against imposition of the death penalty which is absolutely bog standard in many extradition proceedings.

There is no controversy about it, and it is really quick and easy to do. It is a template: you just fill in the details and whiz off the diplomatic note. It takes 5 minutes.

I do not believe the Biden administration is failing to provide the assurance against the death penalty because they wish to execute Julian Assange. They do not need to execute him. They can entomb him in a tiny concrete cell, living a totally solitary existence in a living hell. Arguably, he is of more value alive that way as a terrible warning to other journalists, rather than an executed martyr.

I view the failure so far to produce a guarantee against the death penalty as the clearest evidence that the Biden administration is trying simply to kick this back past the election. By not providing the assurance, already they have achieved a delay of another few weeks which they have been given to provide the assurance, and then further time until the hearing on 20 May to discuss whether assurances produced have been adequate. Not giving the death penalty assurance is simply a stalling tactic, and I am sure they will go right up to the deadline given by the court and then provide it.

The second assurance requested by the court is actually much more interesting. They have requested an assurance that Julian Assange will be able to plead a First Amendment defence on freedom of expression and will not be prevented from doing so on the grounds of his Australian nationality.

The problem which the United States faces is that it is the federal judge who will decide whether or not Julian is entitled to plead that his freedom of speech is protected by the First Amendment. Neither the Department of Justice nor the State Department can bind the judge by an assurance.

The problem was flagged up by the US prosecutor in this case who stated that it is open to the prosecution to argue that a foreign national, operating abroad as Julian did, does not have First Amendment rights. It is extremely important to understand why this was said.

The prisoners in Guantanamo Bay are deemed not to have any constitutional rights, despite being under the power of the US authorities, because they were non-US citizens acting abroad.

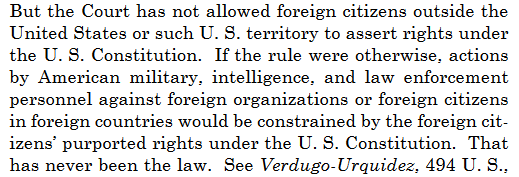

A key US Supreme Court judgment in the case of USAID versus Open Society stated unequivocally that non-US citizens acting abroad do not have First Amendment protection. At first sight that decision appears to have little relevance. It concerns foreign charities in receipt of US aid funds which, as a condition of aid, they must oppose sex work. They attempted to claim this was in breach of First Amendment rights but the Supreme Court ruled that, as foreigners acting abroad, they did not have any such rights.

While that may appear of limited relevance, referring to NGOs not individuals, there is a paragraph in the Open Society judgment which states as a rationale that were First Amendment rights to be granted to those NGOs they would also have to be granted to foreigners with whom the US military and intelligence services were in contact – i.e. the Guantanamo problem.

This paragraph of the Supreme Court ruling appears inescapable in the Assange case:

Julian was a foreign national operating abroad when the Wikileaks material was published. So I do not see how the United States can simply give an assurance on this point, and indeed it seems to me very likely that Julian would indeed be denied First Amendment rights at trial in the United States.

The sensible solution would of course be that as a non-US citizen publishing material outside the United States, Julian should not be subject to US jurisdiction at all. But that will not be adopted.

So I anticipate the United States will produce an assurance which tries to fudge this. They will probably give an assurance that the prosecutor will not attempt to argue that Julian has no First Amendment rights. But that cannot prevent the judge from ruling that he does not, especially as there is a Supreme Court judgement to rely on.

In May when we come to the hearing on the permitted points of appeal, it is vital to understand that there will be two parts to the argument. The first part will be to consider whether the assurances received by diplomatic note from the United States are sufficient for the grounds of appeal to fall completely.

However if it is decided that the assurances from the United States are insufficient, that does not automatically mean that the appeal succeeds. It just means that the appeal is heard. The court will then decide whether the death penalty or nationality discrimination points are strong enough to stop the extradition.

The absence of the death penalty assurance should end the extradition process. But the hearing would see the prosecution argue that it is not necessary, as there are no capital charges currently and none are likely to be added. The judges could go with this, given the undisguised bias towards the United States throughout.

The state will again kick in with its iron resolve to crush Julian. I don’t think that the United States will be able, for the reasons I have given, to provide assurances on the nationality and First Amendment rights, but I think the court will nonetheless order extradition.

The United States will argue that it is a free country with a fair trial system and independent judges and that Julian will be allowed to make the argument in court that he should have First Amendment rights. The UK court should accept that the US judge will come to a fair decision which protects all human rights considerations. They will say that it is perfectly reasonable and normal for states to treat citizens and foreign nationals abroad in different ways in different contexts, including consular protection.

A justice system which is capable of ruling that a person should be handed over to his attempted kidnapper, because then the kidnapper does not have to kidnap him, and ruling that the clauses of the very treaty under which somebody is being extradited do not apply, is capable of accepting that the ability to argue in court for a First Amendment defence is sufficient, even if that defence is likely to be denied.

There is, however, plenty of meat in those questions that would allow another adjourned hearing, another long delay for a judgment and plenty of leeway to get past the November election for Genocide Joe.

The British establishment continues to move inexorably towards ordering Julian’s extradition at the time of its choosing. Once extradition is ordered, Julian in theory has an opportunity to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights.

The European Court of Human Rights can delay the extradition until it hears the case by a section 39 order. But there are two flaws: firstly the extradition may be carried out immediately upon the court judgement before a section 39 order can be obtained, which would take at least 48 hours. Secondly the Rwanda Safety Act has provision, though specifically in the Rwanda context, for the government to ignore section 39 orders from the ECHR.

It cannot be ruled out that the British government would simply extradite Julian even in the face of an ECHR hearing. That would be popular with the Conservative base and, given Starmer’s extremely extensive and dubious role in the Assange saga while Director of Public Prosecutions, I certainly do not put it past him either. It is worth noting that there have been several occasions in recent years when the Home Office has deported people despite British court orders putting a stay on the deportation. There has never been any consequence other than a verbal rap on the knuckles for the Secretary of State from the court.

So the struggle goes on. It is a fight for freedom of speech, it is a fight for freedom of the press, and above all it is a fight for the right of you and me to know the crimes that our governments commit, in our name and with our money.

I am ever more struck by the fact that in fighting for Julian I am fighting exactly the same power structures and adversaries who are behind the genocide in Gaza.

I need to close with an appeal. Please do not stop reading. You will recall that I recently addressed the UN Human Rights Committee on Julian’s case and in doing so had the opportunity to state a few hard truths about the war crimes of the United States.

My opportunity to do so was organised by the Swiss NGO Justice For All International, who submitted a shadow report (open link and click on red icon) by their lawyers to the UN 7 year Periodic Review of the UK’s human rights record. Justice For All also carried out a great deal of lobbying activity in connection with this to get me onto that stage and into meetings with key officials.

I had agreed a fee to pay Justice For All for this legal and lobbying activity, in the expectation that it would be met from the substantial funds held by the bodies comprising the US/European institutions of Julian Assange campaign.

Unfortunately the Assange campaign has refused to meet the bill and I have been left holding it.

I have been told that I failed to follow correct procedures to apply for the spending. I am frankly in shock and a form of grief, because I thought we were friends working for a common cause, in my own case for free. I am reminded of the brilliant perception of Eric Hoffer: “Every great cause begins as a movement and becomes a business”.

I am left with this bill I cannot pay for the work at the UN. Justice For All could not have been nicer about the situation, but if you could contribute to this Justice For All crowdfunder, I should be very grateful.

Read original article and much more and hopefully contribute to Craigs mammoth efforts in Craig’s Blog