On the 9th September 2020, Craig Murray summarised Day 7

CLIVE STAFFORD SMITH

This morning we went straight in to the evidence of Clive Stafford Smith, a dual national British/American lawyer licensed to practice in the UK. He had founded Reprieve in 1999 originally to oppose the death penalty, but after 2001 it had branched out into torture, illicit detention and extraordinary rendition cases in relation to the “war on terror”.

Clive Stafford Smith testified that the publication by Wikileaks of the cables had been of great utility to litigation in Pakistan against illegal drone strikes. As Clive’s witness statement put it at paras 86/7:

86. One of my motivations for working on these cases was that the U.S. drone campaign appeared to be horribly mismanaged and was resulting in paid informants giving false information about innocent people who were then killed in strikes. For example, when I shared the podium with Imran Khan at a “jirga” with the victims of drone strikes, I said in my public remarks that the room probably contained one or two people in the pay of the CIA. What I never guessed was that not only was this true but that the informant would later make a false statement about a teenager who attended the jirga such that he and his cousin were killed in a drone strike three days later. We knew from the official press statement afterwards that the “intelligence” given to the U.S. involved four “militants” in a car; we knew from his family just him and his cousin going to pick up an aunt. There is a somewhat consistent rule that can be seen at work here: it is, of course, much safer for any informant to make a statement about someone who is a “nobody”, than someone who is genuinely dangerous.

87. This kind of horrific action was provoking immense anger, causing America’s status in Pakistan to plummet, and was making life more dangerous for Americans, not less.

Legal action dependent on the evidence about US drones strike policy revealed by Wikileaks had led to a judgement against assassination by the Chief Justice of Pakistan and to a sea change to public attitudes to drone strikes in Waziristan. One result had been a stopping of drone strikes in Waziristan.

Wikileaks released cables also revealed US diplomatic efforts to block international investigation into cases of torture and extraordinary rendition. This ran counter to the legal duty of the United States to cooperate with investigation of allegations of torture as mandated in Article 9 of the UN Convention Against Torture.

Stafford Smith continued that an underrated document released by Wikileaks was the JPEL, or US military Joint Priority Effects List for Afghanistan, in large part a list of assassination targets. This revealed a callous disregard of the legality of actions and a puerile attitude to killing, with juvenile nicknames given to assassination targets, some of which nicknames appeared to indicate inclusions on the list by British or Australian agents.

Stafford Smith gave the example of Bilal Abdul Kareem, an American citizen and journalist who had been the subject of five different US assassination attempts, using hellfire missiles fired from drones. Stafford Smith was engaged in ongoing litigation in Washington on whether “the US Government has the right to target its own citizens who are journalists for assassination.”

Stafford Smith then spoke of Guantanamo and the emergence of evidence that many detainees there are not terrorists but had been swept up in Afghanistan by a system dependent on the payment of bounties. The Detainee Assessment Briefs released by Wikileaks were not independent information but internal US Government files containing the worst allegations that the US had been able to “confect” against prisoners including Stafford Smith’s clients, and often get them to admit under torture.

These documents were US government allegations and when Wikileaks released them it was his first thought that it was the US Government who had released them to discredit defendants. The documents could not be a threat to national security.

Inside Guantanamo a core group of six detainees had turned informant and were used to make false allegations against other detainees. Stafford Smith said it was hard to blame them – they were trying to get out of that hellish place like everybody else. The US government had revealed the identities of those six, which put into perspective their concern for protecting informants in relation to Wikileaks releases.

Clive Stafford Smith said he had been “profoundly shocked” by the crimes committed by the US government against his clients. These included torture, kidnapping, illegal detention and murder. The murder of one detainee at Baghram Airport in Afghanistan had been justified as a permissible interrogation technique to put fear into other detainees. In 2001, he would never have believed the US Government could have done such things.

Stafford Smith spoke of use of Spanish Inquisition techniques, such as strapado, or hanging by the wrists until the shoulders slowly dislocate. He told of the torture of Binyam Mohamed, a British citizen who had his genitals cut daily with a razor blade. The British Government had avoided its legal obligations to Binyam Mohamed, and had leaked to the BBC the statement he had been forced to confess to under torture, in order to discredit him.

At this point Baraitser intervened to give a five minute warning on the 30 minute guillotine on Stafford Smith’s oral evidence. Asked by Mark Summers for the defence how Wikileaks had helped, Stafford Smith said that many of the leaked documents revealed illegal kidnapping, rendition and torture and had been used in trials. The International Criminal Court had now opened an investigation into war crimes in Afghanistan, in which decision Wikileaks released material had played a part.

Mark Summers asked what had been the response of the US Government to the opening of this ICC investigation. Clive Stafford Smith stated that an Executive Order had been issued initiating sanctions against any non-US citizen who cooperated with or promoted the ICC investigation into war crimes by the US. He suggested that Mr Summers would now be subject to US sanction for promoting this line of questioning.

Mr Stafford Smith’s 30 minutes was now up. You can read his full statement here. There could not have been a clearer example from the first witness of why so much time yesterday was taken up with trying to block the evidence of defence witnesses from being heard. Stafford Smith’s evidence was breathtaking stuff and clearly illustrated the purpose of the time guillotine on defence evidence. This is not material governments wish to be widely aired.

James Lewis QC then cross-examined Clive Stafford Smith for the prosecution. He noted that references to Wikileaks in Stafford Smith’s written evidence were few and far between. He suggested that Stafford Smith’s evidence had tended to argue that Wikileaks disclosures were in the public interest; but there was specifically no public interest defence allowed in the UK Official Secrets Act.

Stafford Smith replied that may be, but he knew that was not the case in America.

Lewis then said that in Stafford Smith’s written evidence paras 92-6 he had listed specific Wikileaks cables which related to disclosure of drone policy. But publication of these particular cables did not form part of the indictment. Lewis read out part of an affidavit from US Assistant Attorney Kromberg which stated that Assange was being indicted only for cables containing the publication of names of informants.

Stafford Smith replied that Kromberg may state that, but in practice that would not be the case in the United States. The charge was of conspiracy, and the way such charges were defined in the US system would allow the widest inclusion of evidence. The first witness at trial would be a “terrorism expert” who would draw a wide and far reaching picture of the history of threat against the USA.

Lewis asked whether Stafford Smith had read the indictment. He replied he had read the previous indictment, but not the new superseding indictment.

Lewis stated that the cables Stafford Smith quoted had been published by the Washington Post and the New York Times before they were published by Wikileaks. Stafford Smith responded that was true, but he understood those newspapers had obtained them from Wikileaks. Lewis then stated that the Washington Post and New York Times were not being prosecuted for publishing the same information; so how could the publication of that material be relevant to this case?

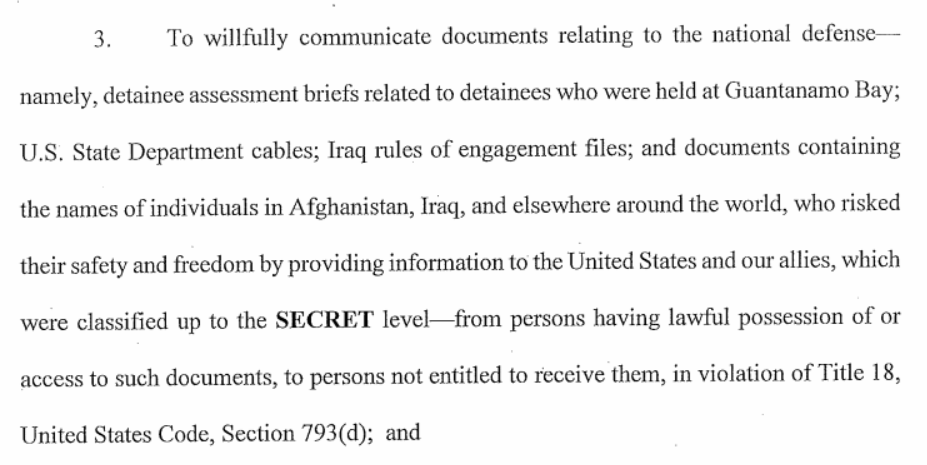

Lewis quoted Kromberg again:

“The only instance in which the superseding indictment encompasses the publication of documents, is where those documents contains names which are put at risk”.

Stafford Smith again responded that in practice that was not how the case would be prosecuted in the United States. Lewis asked if Stafford Smith was calling Kromberg a liar.

At this point Julian Assange called out from the dock “This is nonsense. Count 1 states throughout “conspiracy to publish”. After a brief adjournment, Baraitser warned Julian he would be removed from the court if he interrupted proceedings again.

Stafford Smith said he had not said that Kromberg was a liar, and had not seen the full document from which Lewis was selectively quoting at him. Count 1 of the indictment is conspiracy to obtain national security information and this references dissemination to the public in a sub paragraph. This was not limited in the way Kromberg suggests and his claim did not correspond to Stafford Smith’s experience of how national security trials are in fact prosecuted in the United States.

Lewis reiterated that nobody was being prosecuted for publishing except Assange, and this only related to publishing names. He then asked Stafford Smith whether he had ever been in a position of responsibility for classifying information, to which he got a negative reply. Lewis then asked if had ever been in an official position to declassify documents. Stafford Smith replied no, but he held US security clearance enabling him to see classified material relating to his cases, and had often applied to have material declassified.

Stafford Smith stated that Kromberg’s assertion that the ICC investigation was a threat to national security was nonsense [I confess I am not sure where this assertion came from or why Stafford Smith suddenly addressed it]. Lewis suggested that the question of harm to US national interest from Assange’s activities was best decided by a jury in the United States. The prosecution had to prove damage to the interests of the US or help to an enemy of the US.

Stafford Smith said that beyond the government adoption of torture, kidnapping and assassination, he thought the post-2001 mania for over-classification of government information was an even bigger threat to the American way of life. He recalled his client Moazzam Begg – the evidence of Moazzam’s torture was classified “secret” on the grounds that knowledge that the USA used torture would damage American interests.

Lewis then took Stafford Smith to a passage in the book “Wikileaks; Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy”, in which Luke Harding stated that he and David Leigh were most concerned to protect the names of informants, but Julian Assange had stated that Afghan informants were traitors who merited retribution. “They were informants, so if they got killed they had it coming.” Lewis tried several times to draw Stafford Smith into this, but Stafford Smith repeatedly said he understood these alleged facts were under dispute and he had no personal knowledge.

Lewis concluded by again repeating that the indictment only covered the publication of names. Stafford Smith said that he would eat his hat if that was all that was introduced at trial.

In re-examination, Mark Summers said that Lewis had characterised the disclosure of torture, killing and kidnapping as “in the public interest”. Was that a sufficient description? Stafford Smith said no, it was also the provision of evidence of crime; war crime and illegal activity.

Summers asked Stafford Smith to look at the indictment as a US lawyer (which Stafford Smith is) and see if he agreed with the characterisation by Lewis that it only covered publication where names were revealed. Summers read out this portion of the superseding indictment:

and pointed out that the “and” makes the point on documents mentioning names an additional category of document, not a restriction on the categories listed earlier. You can read the full superseding indictment here; be careful when browsing as there are earlier superseding indictments; the US Government changes its indictment in this case about as often as Kim Kardashian changes her handbag.

Summers also listed Counts 4, 7, 10, 13 and 17 as also not limited to the naming of informants.

Stafford Smith again repeated his rather different point that in practice Kromberg’s assertion does not actually match how such cases are prosecuted in the US anyway. In answer to a further question, he repeated that the US government had itself released the names of its Guantanamo Bay informants.

In regard to the passage quoted from David Leigh, Summers asked Stafford Smith “Do you know that Mr Harding has published untruths in the press”. Lewis objected and Summers withdrew (although this is certainly true).

This concluded Clive Stafford Smith’s evidence. Before the next witness, Lewis put forward an argument to the judge that it was beyond dispute that the new indictment only related, as far as publication being an offence was concerned, to publication of names of defendants. Baraitser had replied that plainly this was disputed and the matter would be argued in due course.

PROFESSOR MARK FELDSTEIN

The afternoon resumed the evidence of Professor Mark Feldstein, begun sporadically amid technical glitches on Monday. For that reason I held off reporting the false start until now; I here give it as one account. Prof Feldstein’s full witness statement is here.

Professor Feldstein is Chair of Broadcast Journalism at Maryland University and had twenty years experience as an investigative journalist.

Feldstein stated that leaking of classified information happens with abandon in the United States. Government officials did it frequently. One academic study estimated such leaks as “thousands upon thousands”. There were journalists who specialised in national security and received Pulitzer prizes for receiving such leaks on military and defence matters. Leaked material is published on a daily basis.

Feldstein stated that “The first amendment protects the press, and it is vital that the First Amendment does so, not because journalists are privileged, but because the public have the right to know what is going on”. Historically, the government had never prosecuted a publisher for publishing leaked secrets. They had prosecuted whistleblowers.

There had been historical attempts to prosecute individual journalists, but all had come to nothing and all had been a specific attack on a perceived Presidential enemy. Feldstein had listed three instances of such attempts, but none had reached a grand jury.

[This is where the technology broke down on Monday. We now resume with Tuesday afternoon.]

Mark Summers asked Prof Feldstein about the Jack Anderson case. Feldstein replied he had researched this for his book “Poisoning the Press”. Nixon had planned to prosecute Anderson under the Espionage Act but had been told by his Attorney General the First Amendment made it impossible. Consequently Nixon had conducted a campaign against Anderson that included anti-gay smears, planting a spy in his office and foisting forged documents on him. An assassination plot by poison had even been discussed.

Summers took Feldstein to his evidence on “Blockbuster” newspaper stories based on Wikileaks publications:

- A disturbing videotape of American soldiers firing on a crowd from a helicopter above Baghdad, killing at least 18 people; the soldiers laughed as they targeted unarmed civilians, including two Reuters journalists.

- US officials gathered detailed and often gruesome evidence that approximately 100,000 civilians were killed after its invasion of Iraq, contrary to the public claims of President George W. Bush’s administration, which downplayed the deaths and insisted that such statistics were not maintained. Approximately 15,000 of these civilians killings had never been previously disclosed anywhere.

- American forces in Iraq routinely turned a blind eye when the US-backed government there brutalized detainees, subjecting them to beatings, whippings, burnings, electric shock, and sodomy.

- After WikiLeaks published vivid accounts compiled by US diplomats of rampant corruption by Tunisian president Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali and his family, ensuing street protests forced the dictator to flee to Saudia Arabia. When the unrest in Tunisia spread to other Mideast countries,WikiLeaks was widely hailed as a key catalyst for this “Arab Spring.”

- In Afghanistan, the US deployed a secret “black” unit of special forces to hunt down “high value” Taliban leaders for “kill or capture” without trial.

- The US government expanded secret intelligence collection by its diplomats at the United Nations and overseas, ordering envoys to gather credit card numbers, work schedules, and frequent flier numbers of foreign dignitaries—eroding the distinction between foreign service officers and spies.

- Saudi Arabian King Abdullah secretly implored the US to “cut off the head of the snake” and stop Iran from developing nuclear weapons even as private Saudi donors were the number-one source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide.

- Customs officials caught Afghanistan’s vice president carrying $52 million in unexplained cash during a trip abroad, just one example of the endemic corruption at the highest levels of the Afghan government that the US has helped prop up.

- The US released “high risk enemy combatants” from its military prison in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba who then later turned up again in Mideast battlefields. At the same time, Guantanamo prisoners who proved harmless—such as an 89-year-old Afghan villager suffering from senile dementia—were held captive for years.

- US officials listed Pakistan’s intelligence service as a terrorist organization and found that it had plotted with the Taliban to attack American soldiers in Afghanistan—even though Pakistan receives more than $1 billion annually in US aid. Pakistan’s civilian president, Asif Ali Zardari, confided that he had limited control to stop this and expressed fear that his own military might “take me out.”

Feldstein agreed that many of these had revealed criminal acts and war crimes, and they were important stories for the US media. Summers asked Feldstein about Assange being charged with soliciting classified information. Feldstein replied that gathering classified information is “standard operating procedure” for journalists. “My entire career virtually was soliciting secret documents or records”

Summers pointed out that one accusation was that Assange helped Manning cover her tracks by breaking a password code. “Trying to help protect your source is a journalistic obligation” replied Feldstein. Journalists would provide sources with payphones, fake email accounts, and help them remove fingerprints both real and digital. These are standard journalistic techniques, taught at journalism college and workshops.

Summers asked about disclosure of names and potential harm to people. Feldstein said this was “easy to assert, hard to establish”. Government claims of national security damage were routinely overblown and should be treated with scepticism. In the case of the Pentagon Papers, the government had claimed that publication would identify CIA agents, reveal military plans and lengthen the Vietnam War. These claims had all proven to be untrue.

On the White House tapes Nixon had been recorded telling his aides to “get” the New York Times. He said their publications should be “cast in terms of aid and comfort to the enemy”.

Summers asked about the Obama administration’s attitude to Wikileaks. Feldstein said that there had been no prosecution after Wikileaks’ major publications in 2010/11. But Obama’s Justice Department had instigated an “aggressive investigation”. However they concluded in 2013 that the First Amendment rendered any prosecution impossible. Justice Department Spokesman Matthew Miller had published that they thought it would be a dangerous precedent that could be used against other journalists and publications.

With the Trump administration everything had changed. Trump had said he wished to “put reporters in jail”. Pompeo when head of the CIA had called Wikileaks a “hostile intelligence agency”. Sessions had declared prosecuting Assange “a priority”.

James Lewis then rose to cross-examine Feldstein. He adopted a particularly bullish and aggressive approach, and started by asking Feldstein to confine himself to very short, concise answers to his precise questions. He said that Feldstein “claimed to be” an expert witness, and had signed to affirm that he had read the criminal procedural rules. Could he tell the court what those rules said?

This was plainly designed to trip Feldstein up. I am sure I must have agreed WordPress’s terms and conditions in order to be able to publish this blog, but if you challenged me point blank to recall what they say I would struggle. However Feldstein did not hesitate, but came straight back saying that he had read them, and they were rather different to the American rules, stipulating impartiality and objectivity.

Lewis asked what Feldstein’s expertise was supposed to be. Feldstein replied the practice, conduct and history of journalism in the United States. Lewis asked if Feldstein was legally qualified. Feldstein replied no, but he was not giving legal opinion. Lewis asked if he had read the indictment. Feldstein replied he had not read the most recent indictment.

Lewis said that Feldstein had stated that Obama decided not to prosecute whereas Trump did. But it was clear that the investigation had continued through from the Obama to the Trump administrations. Feldstein replied yes, but the proof of the pudding was that there had been no prosecution under Obama.

Lewis referred to a Washington Post article from which Feldstein had quoted in his evidence and included in his footnotes, but had not appended a copy. “Was that because it contained a passage you do not wish us to read?” Lewis said that Feldstein had omitted the quote that “no formal decision had been made” by the Obama administration, and a reference to the possibility of prosecution for activity other than publication.

Feldstein was plainly slightly rattled by Lewis’ accusation of distortion. He replied that his report stated that the Obama administration did not prosecute, which was true. He had footnoted the article; he had not thought he needed to also provide a copy. He had exercised editorial selection in quoting from the article.

Lewis said that from other sources, a judge had stated in District Court that investigation was ongoing and District Judge Mehta had said other prosecutions against persons other than Manning were being considered. Why had Feldstein not included this information in his report? Assange’s lawyer Barry J Pollock had stated “they are not informing us they are closing the investigation or have decided not to charge.” Would it not be fair to add that to his report?

Prof Feldstein replied that Assange and his lawyers would be hard to convince that the prosecution had been dropped, but we know that no new information had in 2015/16 been brought to the Grand Jury.

Lewis stated that in 2016 Assange had offered to go to the United States to face charges if Manning were granted clemency. Does this not show the Obama administration was intending to charge? Should this not have been in his report? Feldstein replied no, because it was irrelevant. Assange was not in a position to know what Obama’s Justice Department was doing. The subsequent testimony of Obama Justice Department insiders was much more valuable.

Lewis asked if the Obama administration had decided not to prosecute, why would they keep the Grand Jury open? Feldstein replied this happened very frequently. It could be for many reasons, including to collect information on alleged co-conspirators, or simply in the hope of further new evidence.

Lewis suggested that the most Feldstein might honestly say was that the Obama administration had intimated that they would not prosecute for passively obtained information, but that did not extend to a decision not to prosecute for hacking with Chelsea Manning. “If Obama did not decide not to prosecute, and the investigation had continued into the Trump administration, then your diatribe against Trump becomes otiose.”

Lewis continued that the “New York Times problem” did not exist because the NYT had only published information it had passively received. Unlike Assange, the NYT had not conspired with Manning illegally to obtain the documents. Would Prof Feldstein agree that the First Amendment did not defend a journalist against a burglary or theft charge? Feldstein replied that a journalist is not above the law. Lewis then asked Feldstein whether a journalist had a right to “steal or unlawfully obtain information” or “to hack a computer to obtain information.” Each time Feldstein replied “no”.

Lewis then asked if Feldstein accepted that Bradley (sic) Manning had committed a crime. Feldstein replied “yes”. Lewis then asked “If Assange aided and abetted, consulted or procured or entered into a conspiracy with Bradley Manning, has he not committed a crime?” Feldstein said that would depend on the “sticky details.”

Lewis then restated that there was no allegation that the NYT entered into a conspiracy with Bradley Manning, only Julian Assange. On the indictment, only counts 15, 16 and 17 related to publishing and these only to publishing of unredacted documents. The New York Times, Guardian and Washington Post had united in condemnation of the publication by Wikileaks of unredacted cables containing names. Lewis then read out again the same quote from the Leigh/Harding book he had put to Stafford Smith, stating that Julian Assange had said the Afghan informants would deserve their fate.

Lewis asked: “Would a responsible journalist publish unredacted names of an informant knowing he is in danger when it is unnecessary to do so for the purpose of the story”. Prof Feldstein replied “no”. Lewis then went on to list examples of information it might be proper for government to keep secret, such as “troop movements in war, nuclear codes, material that would harm an individual” and asked if Feldstein agreed these were legitimate secrets. Feldstein replied “yes”.

Lewis then asked rhetorically whether it was not more fair to allow a US jury to be the judge of harm. He then asked Feldstein: “You say in your report that this is a political prosecution. But a Grand jury has supported the prosecution. Do you accept that there is an evidentiary basis for the prosecution?”. Feldstein replied “A grand jury has made that decision. I don’t know that it is true.” Lewis then read out a statement from US Assistant Attorney Kromberg that prosecution decisions are taken by independent prosecutors who follow a code that precludes political factors. He asked Feldstein if he agreed that independent prosecutors were a strong bulwark against political prosecution.

Feldstein replied “That is a naive view.”

Lewis then asked whether Feldstein was claiming that President Trump or his Attorney General had ordered this prosecution without a factual basis. The professor replied he had no doubt it was a political prosecution, this was based on 1) its unprecedented nature 2) the rejection of prosecution by Obama but decision to prosecute now with no new evidence 3) the extraordinary wide framing of the charges 4) President Trump’s narrative of hostility to the press. “It’s political”.

Mark Summers then re-examined Professor Feldstein. He said that Lewis had suggested that Assange was complicit in Manning obtaining classified information but the New York Times was not. Is it your understanding that to seek to help an official leaker is a crime? Professor Feldstein replied “No, absolutely not”.

“Do journalists ask for classified information?”

“Yes.”

“Do journalists solicit such information?”

“Yes.”

“Are you aware of any kind of previous prosecution for this kind of activity.”

“No. Absolutely not.”

“Could you predict it would be criminalised?”

“No, and it is very dangerous.”

Summers than asked Professor Feldstein what the New York Times had done to get the Pentagon Papers from Daniel Ellsberg. Feldstein replied they were very active in soliciting the papers. They had a key to the room that held the documents and had helped to copy them. They had played an active not a passive role. “Journalists are not passive stenographers.”

Summers reminded Prof Feldstein that he had been asked about hacking. What if the purpose of the hacking was not to obtain the information, but to disguise the source? This was the specific allegation spelt out in Kromberg memorandum 4 paras 11 to 14. Professor Feldstein replied that protecting sources is an obligation. Journalists work closely with, conspire with, cajole, encourage, direct and protect their sources. That is journalism.

Summers asked Prof Feldstein if he maintained his caution in accepting government claims of harm. Feldstein replied absolutely. The government track record demanded caution. Summers pointed out that there is an act which specifically makes illegal the naming of intelligence sources, the Intelligence Identities Protection Act. Prof Feldstein said this was true; the fact that the charge was not brought under the IIPA proves that it is not true that the prosecution is intended to be limited to revealing of identities and in fact it will be much broader.

Summers concluded by saying that Lewis had stated that Wikileaks had released the unredacted cables in a mass publication. Would it change the professor’s assessment if the material had already been released by others. Prof Feldstein said his answers were not intended to indicate he accepted the government narrative.

Edward Fitzgerald QC then took over for the defence. He put to Prof Feldstein that there had been no prosecution of Assange when Manning was prosecuted, and Obama had given Manning clemency. These were significant facts. Feldstein agreed.

Fitzgerald then said that the Washington Post article from which Lewis complained Feldstein had quoted selectively, contained a great deal more material Feldstein had also not quoted but which strongly supported his case, for example “Officials told the Washington Post last week that there is no sealed indictment and the Department had “all but concluded that they would not bring a charge.”” It further stated that when Snowden was charged, Greenwald was not, and the same approach was followed with Manning/Assange. So overall the article confirmed Feldstein’s thesis, as contained in his report. Feldstein agreed. There was then discussion of other material that could have been included to support his thesis.

Fitzgerald concluded by asking if Feldstein were familiar with the phrase “a grand jury would indict a ham sandwich”. Feldstein replied it was common parlance and indicated the common view that grand juries were malleable and almost always did what prosecutors asked them to do. There was a great deal of academic material on this point.

THOUGHTS

Thus concluded another extraordinary day. Once again, there were just five of us in the public gallery (in 42 seats) and the six allowed in the overflow video gallery in court 9 was reduced to three, as three seats were reserved by the court for “VIPs” who did not show up.

The cross-examinations showed the weakness of the thirty minute guillotine adopted by Baraitser, with really interesting defence testimony cut short, and then unlimited time allowed to Lewis for his cross examination. This was particularly pernicious in the evidence of Mark Feldstein. In James Lewis’ extraordinary cross-examination of Feldstein, Lewis spoke between five and ten times as many words as the actual witness. Some of Lewis’s “questions” went on for many minutes, contained huge passages of quote and often were phrased in convoluted double negative. Thrice Feldstein refused to reply on grounds he could not make out where the question lay. With the defence initial statement of the evidence limited to half an hour, Lewis’s cross examination approached two hours, a good 80% of which was Lewis speaking.

Feldstein was browbeaten by Lewis and plainly believed that when Lewis told him to answer in very brief and concise answers, Lewis had the authority to instruct that. In fact Lewis is not the judge and it was supposed to be Feldstein’s evidence, not Lewis’s. Baraitser failed to protect Feldstein or to explain his right to frame his own answers, when that was very obviously a necessary course for her to take.

Today we had two expert witnesses, who had both submitted lengthy written testimony relating to one indictment, which was now being examined in relation to a new superseding indictment, exchanged at the last minute, and which neither of them had ever seen. Both specifically stated they had not seen the new indictment. Furthermore this new superseding indictment had been specifically prepared by the prosecution with the benefit of having heard the defence arguments and seen much of the defence evidence, in order to get round the fact that the indictment on which the hearing started was obviously failing.

On top of which the defence had been refused an adjournment to prepare their defence against the new indictment, which would have enabled these and other witnesses to see the superseding indictment, adjust their evidence accordingly and be prepared to be cross-examined in relation to it.

Clive Stafford Smith testified today that in 2001 he would not have believed the outrageous crimes that were to be perpetrated by the US government. I am obliged to say that I simply cannot believe the blatant abuse of process that is unfolding before my eyes in this courtroom.

Read Original article and contribute to Craig’s capacity to report at Craig’s blog