On the 16th July 2022, Kelly Trantor reports in Declassified Australia on New revelations on the Labor Government’s secret planning to act on the Assange case without offending the Americans.

“Quiet diplomacy”, a “soft approach”, a “loud approach” and “avoiding megaphone diplomacy” have all been floated as strategies to “bring to an end” the case against WikiLeaks founder, Julian Assange. In situations like his, the best form of diplomacy is that which produces results most favourable to the citizen involved and at the same time keeps them safe and in good health.

But government documents obtained this week by Declassified Australia under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act from the Attorney-General’s Department, indicate the new Labor Government does certainly not rule out the physical extradition of Assange from the United Kingdom to the United States, nor does it give any hint about how it might deal with possible fallout from that.

On 15 May 2022, Senator Penny Wong told the National Press Club, “Certainly we would encourage, were we elected, the US Government to bring this matter to a close, but ultimately that is a matter for the Administration.” Daniel Hurst, journalist at the Guardian Australia, attempted to seek clarity on what ‘bring this matter to a close’ meant but the question went unanswered.

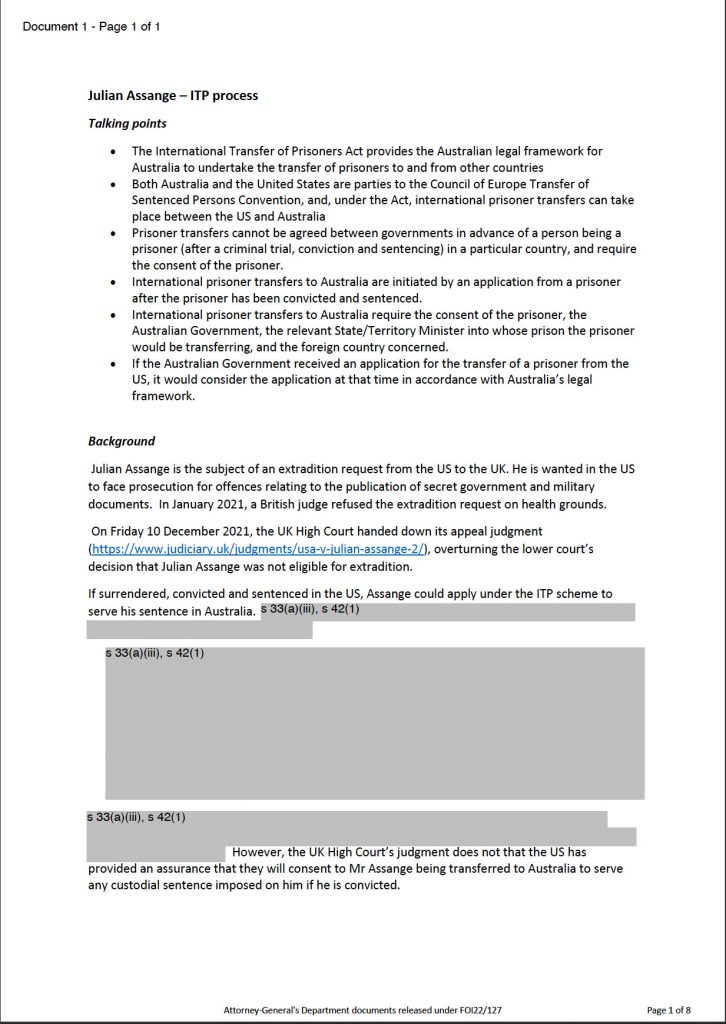

The FOI documents obtained include ‘Talking Points’ prepared for the Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus on 2 June 2022 titled, ‘Julian Assange – International Transfer of Prisoners process – talking points and background’. They point out that:

Prisoner transfers cannot be agreed between governments in advance of a person being a prisoner (after a criminal trial, conviction and sentencing) in a particular country, and require the consent of the prisoner;

International prisoner transfers to Australia are initiated by an application from a prisoner after the prisoner has been convicted and sentenced;

If surrendered, convicted and sentenced in the US, Assange could apply under the ITP scheme to serve his sentence in Australia;

After some redactions the document continues: However, the UK High Court’s judgment does note that the US has provided an assurance that they will consent to Mr Assange being transferred to Australia to serve any custodial sentence on him if he is convicted.

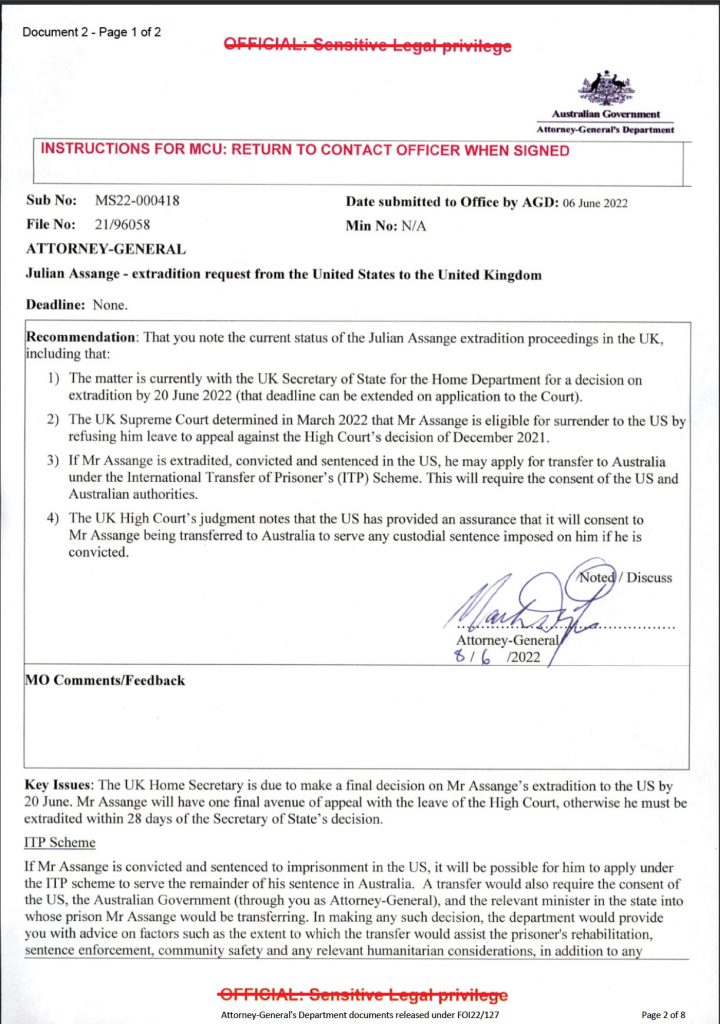

The FOI documents also show that on 8 June 2022, the Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus, signed a ‘Ministerial Submission’ titled ‘Julian Assange – extradition request from the United States to the United Kingdom’ which recommended that the Attorney-General note the current status of the Julian Assange extradition proceedings in the UK, including that:

- The matter is currently with the UK Secretary of State for the Home Department for a decision on the extradition by 20 June 2022 (that deadline can be extended on application to the Court).

- The UK Supreme Court determined in March 2022 that Mr Assange is eligible for surrender to the US by refusing him leave to appeal against the High Court’s decision of December 2021.

- If Mr Assange is extradited, convicted and sentenced in the US, he may apply for transfer to Australia under the International Transfer of Prisoner’s Scheme. This will require the consent of the US and Australian authorities.

- The UK High Court’s judgment notes that the US has provided an assurance that it will consent to Mr Assange being transferred to Australia to serve any custodial sentence imposed on him if he is convicted.

Under the heading ‘Key Issues’ the document notes:

‘The UK Home Secretary is due to make a final decision on Mr Assange’s extradition to the US by 20 June. Mr Assange will have one final avenue of appeal with the leave of the High Court, otherwise he must be extradited within 28 days of the Secretary of State’s decision.’

Furthermore, ‘If Mr Assange is convicted and sentenced to imprisonment in the US, it will be possible for him to apply under the ITP scheme to serve the remainder of his sentence in Australia. A transfer would also require the consent of the US, the Australian Government (through you as Attorney-General), and the relevant minister in the state into whose prison Mr Assange would be transferring.

In making any such decision, the department would provide you with advice on factors such as the extent to which the transfer would assist the prisoner’s rehabilitation, sentence enforcement, community safety and any relevant humanitarian considerations, in addition to any conditions of transfer required by the US.’

Information under the headings ‘Government representations and consulate engagement’ and ‘Key risks and mitigation’ are heavily redacted so one cannot tell whether the Australian Government has specifically asked the United States to drop the case against Assange or taken into account things like Assange’s medical condition. A review by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) has been sought to try to get access to the redacted information.

Presumably, one of the key risks that must be considered by the Australian Government is the risk of suicide.

In the judgment of presiding UK District Judge, Vanessa Baraitser, she outlines the evidence provided by Professor Michael Kopelman, emeritus professor of neuropsychiatry at King’s College London and until 31 May 2015, a consultant neuropsychiatrist at St Thomas’s Hospital, who carried out a comprehensive investigation of Assange’s psychiatric history.

He considered there to be an abundance of known risk factors indicating a very high risk of suicide including the intensity of Mr Assange’s suicidal preoccupation and the extent of his preparations. Importantly, he stated:

“I am as confident as a psychiatrist ever can be that, if extradition to the United States were to become imminent [emphasis added], Mr Assange will find a way of suiciding.”

It is worth noting that the District Judge, Vanessa Baraitser, accepted the medical opinion of Professor Kopelman and found him to be ‘impartial’ and ‘dispassionate’.

If the extradition in and of itself is a trigger for suicide, then any discussions about where Assange may be housed on US soil pre- and post-trial and under what restrictive measures becomes completely immaterial.

The presence of large redactions in the documents may suggest that, despite the medical evidence, the government has not ruled out the extradition of Assange to US soil.

The imprecise language of the Labor government statements on using “quiet diplomacy” to “bring the matter to a close”, rather than clearly saying what they are seeking, may be giving false hope to the Australian public. Without putting forward its “quiet diplomacy” in non-negotiable terms to the US, it may be that the dropping of charges will not even be considered.

On 17 June 2022 a Joint Statement of Foreign Minister, Senator Penny Wong, and Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus, was released. It noted that:

We will continue to convey our expectations that Mr Assange is entitled to due process, humane and fair treatment, access to proper medical care, and access to his legal team.

The Australian Government has been clear in our view that Mr Assange’s case has dragged on for too long and that it should be brought to a close. We will continue to express this view to the governments of the United Kingdom and United States.

On 28 June 2022, the Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus, told ABC Radio National’s Law Report that:

The United States has long legislated in an extraterritorial way and I think that all other countries have understood that for a long time.

What we have in the case of Julian Assange is an Australian citizen, who is presently held in a British jail, who is subject to an extradition request made by the United States of America, which has an extradition treaty with the United Kingdom. It is not open to the Australian Government to directly interfere with either the jailing of Mr Assange in the United Kingdom, or the extradition request that’s been made by the United States to the United Kingdom.

What is available to an Australian Government, and the Prime Minister has made this very clear, and I’ve said this as well, we think that the case of Julian Assange has gone on for far too long. What is available to the Australian Government is making diplomatic representations.

But as the Prime Minister has said, those diplomatic representations are best done in private…. it’s about what we can put to the United States Government, which is the moving party here.

If extradited from the UK, and then tried and convicted in the US, Assange faces a cumulative total of up to 175 years imprisonment. His charges attract a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison on each count of violating the US’s Espionage Act of 1917 and a maximum penalty of five years for the single count of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion.

The ‘International Transfer of Prisoners Statement of Policy’ states – among other things – that:

A parole eligibility date will be determined as part of the sentence enforcement in Australia. The earliest possible release date in the sentencing country will be enforced as the parole eligibility date. If an earliest possible release date has not been determined by the sentencing country, Australia will propose a non-parole period that is 66 per cent of the original sentence imposed by the foreign country.

However, if the original sentence imposed by the foreign country significantly exceeds the maximum head sentence that could be imposed in Australia for a similar offence, Australia will propose a non-parole period that equates to 66 per cent of the maximum sentence that could be imposed in Australia for a similar offence.

Release on parole will be discretionary in accordance with the relevant Australian processes and laws. Where possible, the parole eligibility date will be at least 12 months before the sentence expiry date.

Some draw parallels to the case of David Hicks, an Australian who had received militant training in Afghanistan before being detained by US forces in December 2001, and who was subsequently incarcerated in Guantanamo Bay detention camp from 2002 to 2007.

But they place no weight on the fact that Hicks did not want to plead guilty to any offence, in any plea deal to free him. In his book, Guantanamo: My Journey, Hicks wrote:

If I refused to sign these new extra documents the Australian government would not take me. The consular official threatened me with this himself and [lawyer Michael] Mori agreed and said I had no choice. I did not want to sign anything or have anything to do with the commissions or plea deals, but my fear of being left behind was great. Once again I was forced into doing something I did not want to do.

Julian Assange will no doubt take a similarly principled approach in any negotiations and may well refuse to agree to any plea deal.

One can see why a plea to an offence carrying a lower maximum term such as conspiracy to commit computer intrusion, with a non-parole period and sentence to be served in Australia, would be attractive to a new Government which wants to avoid offending an ally and says it is eager to ‘bring the matter to an end’ on negotiated terms without Government pronouncements.

But this requires the Australian Government to accept assurances contradicted by everything the United States has done to Assange for over a decade, and by its previous failure to comply with its own assurances in other cases, to ignore the medical opinion of Professor Kopelman and risk of Assange’s extradition-related suicide, to turn a blind eye to the fact that the US has not adopted or incorporated into its domestic law the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court against the ‘crime against humanity’ of ‘torture’, and to assume that Assange himself will co-operate in the process.

Moreover, Greg Barns SC, Adviser to the Australian Assange Campaign, makes a critical point. He told Declassified Australia that, “The Assange case is unique. One of the ways in which that is the case is the attempted extraterritorial use of the US Espionage Act. The US is seeking to establish a precedent where it could seek to extradite any journalist anywhere in the world for disclosure of US information.

“If Australia were to sanction a ‘deal’ whereby Assange pleaded guilty to a charge in exchange for an Australian served sentence, it would be endorsing that approach.”

At the end of the day, the Australian Government should come clean with the Australian people about what the representations made to the United States, or ‘quiet diplomacy’, actually involve.

Surely we are entitled to see that the Government has done as much for securing Assange’s freedom from our alleged ‘great ally’ as it did for other ‘political detainees’ of non-allied regimes, like Peter Greste jailed in Egypt, and Kylie Moore-Gilbert jailed in Iran.

“Quiet diplomacy” does not mean weak diplomacy.

Is Australia urging the United States in non-negotiable terms to give priority to human rights and press freedom over any intelligence service-based vendetta or US domestic political considerations, and drop the case against Assange completely?

Read original article in Declassified Australia

and other articles on Assange